Pushkin exclaimed with vehemence: "My children will read the Bible with me in the original." "Slavonic?" asked Khomyakov. “In Slavonic,” Pushkin confirmed, “I myself will teach it to them.”

Metropolitan Anastassy (Gribanovsky).

Pushkin in his attitude to religion and the Orthodox Church

The Russian rural school is now obliged to impart knowledge to its pupils... this is such a pedagogical treasure that no rural school in the world possesses. This study, in itself an excellent mental gymnastics, gives life and meaning to the study of the Russian language.

S.A. Rachinsky. rural school

In order for children to continue to master the Slavic literacy, we periodically write texts in this language. We do not sit down at the table and do not write down dictations for the top five, but we do this. For every twelfth holiday, or for a great one, or for a name day, we prepare troparia, kontakia, magnifications written in Church Slavonic on a beautiful cardboard. One child gets one prayer, the other another. Older children themselves write off the text from the prayer book, it is easier for the younger children to circle what was written by their mother. Very small paint the initial letter and the ornamental frame. Thus, all children participate in preparations for the holiday, for the younger ones this is the first acquaintance, for older children - training, for those who already know how to read - consolidation. And we take these leaves to the temple for the vigil to sing along to the choir. At home, on holidays, we also sing troparia, kontakia and magnifications - before meals and during family prayers. And it is very convenient for everyone to look not at the prayer book, where the troparion still needs to be found and it is written in small print, but at the text prepared by the children. Thus, children are regularly engaged, and without suspecting it. Such activities in themselves teach the child to write correctly in this ancient language. Once I suggested that my nine-year-old son write a kontakion for some holiday, but I could not find the Church Slavonic text. I gave him this kontakion in Russian, offering to write it off. And he wrote off, but in Church Slavonic, he himself, according to his own understanding, placing epics at the end of masculine nouns, stress and even aspiration, writing down almost all the necessary words under the titles. As he explained, so much more beautiful. True, his yati and Izhitsa were written in the wrong place, of course, there were mistakes. But in general, a child who had not attended a single class in the Church Slavonic language, who studied it in that primitive form, as described in this article, simply following memory, wrote down an unfamiliar text almost correctly.

To learn a language on a more serious level, of course, you still have to turn to grammar. If you are not satisfied with the method of natural immersion in the language given here, the unobtrusive mastering of knowledge, you can also conduct something similar to the lessons of the Church Slavonic language. Having introduced the child (in this case, who already knows how to read Russian) the Slavic alphabet, we will single out those letters that do not look like modern Russian ones - there are not so many of them. We will ask the child to write them out, we will indicate how they are read. Then we will consider superscript and lowercase characters, including simple and alphabetic titles. Separately, we will analyze the recording of numbers in the Church Slavonic language. If a child already knows how to read in Slavonic, such lessons will not make it difficult for him or his parents. If there is a task to truly study the Church Slavonic language, then in the future you can either purchase textbooks on this subject and master them at home, or go to courses, then to a specialized university ... From textbooks, you can recommend N.P. Sablina "Slavic letter", for older children and parents - self-instruction manual of the Church Slavonic language Yu.B. Kamchatnova, unique in that it was written not for philologists and in an accessible language. But all this will be the study of a language that has already become native.

The "teaching method" described here can not only be implemented in the family - it is designed specifically for the family. After all, the culture of the parental family first of all becomes our native culture, and it is the language of our parents that becomes our native language. School study can give us knowledge, perhaps brilliant - but for a child this knowledge will not become a part of life if it is not part of family life. Home "immersion in the language", of course, will not make the child a specialist - but it will make the Church Slavonic language his native language, whether he will be a specialist in this field of linguistics in the future or will not study language as a subject at all. And most importantly: such home education, even in such a simple form, opens up new opportunities for communication between parents and children, allows them to find new common topics, while not requiring special efforts and time from adults.

Such homework educates parents even more than their students; parents study together with their children, receive unlimited opportunities for free pedagogical creativity, which also brings all family members together. Maybe not in every family this is possible, but everyone can try. Try to make your home a place of education.

C Church Slavonic is a language that has survived to our time as the language of worship. It goes back to the Old Church Slavonic language created by Cyril and Methodius on the basis of South Slavic dialects. The most ancient Slavic literary language spread first among the Western Slavs (Moravia), then among the southern Slavs (Bulgaria), and eventually becomes the common literary language of the Orthodox Slavs. This language also became widespread in Wallachia and some regions of Croatia and the Czech Republic. Thus, from the very beginning, Church Slavonic was the language of the church and culture, and not of any particular people.

Church Slavonic was the literary (bookish) language of the peoples inhabiting a vast territory. Since it was, first of all, the language of church culture, the same texts were read and copied throughout this territory. Monuments of the Church Slavonic language were influenced by local dialects (this was most strongly reflected in spelling), but the structure of the language did not change. It is customary to talk about editions (regional variants) of the Church Slavonic language - Russian, Bulgarian, Serbian, etc.

Church Slavonic has never been a spoken language. As a book, it was opposed to living national languages. As a literary language, it was a standardized language, and the standard was determined not only by the place where the text was rewritten, but also by the nature and purpose of the text itself. Elements of lively colloquial (Russian, Serbian, Bulgarian) could penetrate Church Slavonic texts in one quantity or another. The norm of each specific text was determined by the relationship between the elements of the book and the living spoken language. The more important the text was in the eyes of a medieval Christian scribe, the more archaic and stricter the language norm. Elements of spoken language almost did not penetrate into liturgical texts. The scribes followed tradition and focused on the most ancient texts. In parallel with the texts, there was also business writing and private correspondence. The language of business and private documents combines elements of the living national language (Russian, Serbian, Bulgarian, etc.) and separate Church Slavonic forms. The active interaction of book cultures and the migration of manuscripts led to the fact that the same text was copied and read in different editions. By the XIV century. came the understanding that the texts contain errors. The existence of different editions did not allow us to decide which text is older, and therefore better. At the same time, the traditions of other peoples seemed more perfect. If the South Slavic scribes were guided by Russian manuscripts, then the Russian scribes, on the contrary, believed that the South Slavic tradition was more authoritative, since it was the South Slavs who preserved the features of the ancient language. They valued Bulgarian and Serbian manuscripts and imitated their orthography.

The first grammar of the Church Slavonic language, in the modern sense of the word, is the grammar of Lawrence Zizanias (1596). In 1619, the Church Slavonic grammar of Melety Smotrytsky appeared, which determined the later language norm. In their work, the scribes sought to correct the language and text of the books being copied. At the same time, the idea of what a correct text is has changed over time. Therefore, in different eras, books were corrected either from manuscripts that the editors considered ancient, or from books brought from other Slavic regions, or from Greek originals. As a result of the constant correction of liturgical books, the Church Slavonic language acquired its modern look. Basically, this process was completed at the end of the 17th century, when, at the initiative of Patriarch Nikon, the liturgical books were corrected. Since Russia supplied other Slavic countries with liturgical books, the post-Nikonian appearance of the Church Slavonic language became the general norm for all Orthodox Slavs.

In Russia, Church Slavonic was the language of the Church and culture until the 18th century. After the emergence of a new type of Russian literary language, Church Slavonic remains only the language of Orthodox worship. The corpus of Church Slavonic texts is constantly replenished: new church services, akathists and prayers are being compiled. Being the direct heir of the Old Church Slavonic language, Church Slavonic has retained many archaic features of the morphological and syntactic structure to this day. It is characterized by four types of noun declension, has four past tense verbs and special nominative participle forms. The syntax preserves the tracing Greek turns (dative independent, double accusative, etc.). The spelling of the Church Slavonic language underwent the greatest changes, the final form of which was formed as a result of the "book right" of the 17th century.

Church Slavonic language: how could the saints equal to the apostles convey to the Slavs the meanings for which there were no words?

How did it happen that there can be no actual Russian literary language? Why is it more difficult to translate a liturgy into Russian than into any European language? The answers are in Olga Sedakova's lecture delivered at St. Philaret's Institute on December 2, 2004.

The topic of a short lecture that I want to bring to your attention on this solemn day is "Church Slavonic in Russian culture." I think this is a very relevant topic for those gathered here, especially in connection with the disputes over the modern liturgical language that have been going on in recent years. As you well know, the very existence as a liturgical language began with a sharp controversy.

The real history of the adoption of the Cyrillo-Methodian texts in Rome (the unprecedented introduction of a new vernacular language into liturgical use up to the Reformation!) was studied by Italian Slavists (Riccardo Picchio, Bruno Merigi); As far as I know, their research has not yet been translated into Russian.

So, Church Slavonic as a new language of worship arose in a storm of controversy - and more than once new and new disputes arose around it, including those that call into question the beneficialness of this initial initiative (cf. the opinion of G. Fedotov). But today I would like to talk about the Church Slavonic language, as far as possible detached from the polemics, both past and new.

Church Slavonic belongs not only to church history proper, but to the entire history of Russian culture. Many features of our culture and, as it is called, national mentality can be associated with the thousand-year-old strong presence of this second, “almost native”, “almost understandable” language, “sacred language”, the use of which is limited exclusively to worship.

Any, the shortest quotation in Church Slavonic (I will talk about this later) immediately brings with it the whole atmosphere of temple worship; these words and forms seem to have acquired a special materiality, becoming like temple utensils, objects withdrawn from everyday use (such as, for example, the salary of an icon, the free use of which by a modern artist looks like a scandalous provocation, which we recently witnessed).

However, the attitude towards Church Slavonic quotations in everyday use is softer: such obviously “inappropriate” quotations are experienced as a special game, by no means parodying the sacred text, as a special comedy that does not involve the slightest blasphemy (cf. N. Leskov’s “Soboryan”); however, those who play the game are well aware of its limits.

In comparison with Church Slavonic, in contrast to it, it was perceived as a profane language, not just neutral, but “filthy” (some traces of this derogatory meaning “Russian” were preserved in the dialects: the Vladimir “russify” means to sink, stop looking after yourself), unacceptable to express spiritual content.

In comparison with Church Slavonic, in contrast to it, it was perceived as a profane language, not just neutral, but “filthy” (some traces of this derogatory meaning “Russian” were preserved in the dialects: the Vladimir “russify” means to sink, stop looking after yourself), unacceptable to express spiritual content.

Naturally, this difference in status softened after the creation of the literary Russian language - but did not completely disappear (cf. indignation at the presentation of theological topics in secular language, in the forms of secular poetry: St. Ignatius Brianchaninov about the ode "God" by Derzhavin).

Generally speaking, the Church Slavonic language belongs not only to Russian culture, but to the entire cultural community, which is usually called Slavia Orthodoxa (Orthodox, or Cyrillic Slavs), that is, the Eastern and Southern Slavs (after he left his West Slavic Moravian cradle).

In each of these traditions, Church Slavonic was a second language (that is, one that is mastered not organically, like a native language, but through special study), a written, sacred language (which we have already talked about), a kind of Slavic Latin. It, like Latin, was intended to be a supranational language, which is often forgotten (translating from Church Slavonic as from someone else's "Russian" into one's own, say, Ukrainian - or considering it, as in Bulgaria, "Old Bulgarian").

And immediately it should be noted its difference from Latin. Latin was the language of the whole civilization. Latin was used in business writing, in secular literature, in the everyday life of educated people, oral and written - in a word, in all those areas where the literary language always operates.

As for Church Slavonic, its use from the very beginning was strictly limited: liturgical. Church Slavonic was never spoken! He could not be taught the way Latin was taught: by offering the student to compose the simplest phrases, to translate some phrases from his native language, such as "the boy loves his home."

Such new phrases simply should not have been! They would belong to a genre that Church Slavonic excluded. Exercises here could only be tasks - to compose a new troparion, kontakion, akathist, etc. according to given samples. But it's very unlikely that this would happen.

This second language, "Slavic Latin" (with all the refinements already made and many others) was in each of the Slavic countries very closely related to the first dialect, vernacula, "simple language." So close that he created for a Bulgarian, a Russian, a Serb an impression of intelligibility that did not require special training. Or almost intelligibility: but the vagueness of the meaning of Church Slavonic texts was explained by a person to himself as a “sacred darkness” necessary for a liturgical text.

This impression, however, was and remains false, because, in its essence, Church Slavonic is a different language. We emphasize that it is different not only in relation to modern Russian, but also to no lesser extent to Old Russian dialects. However, its “otherness” was unique: not so much grammatical or vocabulary, but semantic, semantic.

We know that the Church Slavonic “belly” is not like the modern Russian “belly”: it is “life”. But even in ancient Russian dialects, “belly” did not mean “life”, but “property, belongings”. Church Slavonic was, as the historian of the Russian language Alexander Isachenko well said, in essence the Greek language ... yes, a strange metempsychosis of the Greek language into the flesh of Slavic morphemes.

We know that the Church Slavonic “belly” is not like the modern Russian “belly”: it is “life”. But even in ancient Russian dialects, “belly” did not mean “life”, but “property, belongings”. Church Slavonic was, as the historian of the Russian language Alexander Isachenko well said, in essence the Greek language ... yes, a strange metempsychosis of the Greek language into the flesh of Slavic morphemes.

Indeed, the roots, morphemes, grammar were Slavic, but the meanings of the words were largely Greek (recall that initially all liturgical texts were translations from Greek). Based on their linguistic competence, a person simply could not understand these meanings and their combinations.

Having studied another, most likely Greek language, a Slav would certainly not have these semantic illusions (and until now, some dark places in Slavic texts can be clarified in the only way: by referring to the Greek original). In this regard, one can understand the disputes that arose during the approval of the Slavic worship.

Isn’t it dangerous to introduce this new, in the plan of the Slavic Teachers, a more “simple” language (one of the arguments for translating into Slavonic was the “simplicity” - unlearnedness - of the Slavs: “we, the Slavs, are a simple child”, as the Moravian prince wrote, inviting Sts. Cyril and Methodius)?

One of the arguments of the opponents of the innovation was precisely that it would be less intelligible than Greek, or ostensibly intelligible. Opponents of the Slavic worship referred to the words of St. Paul on speaking in tongues: "You who speak in a (new) tongue, pray for the gift of interpretation." The new language will be incomprehensible precisely because it is too close - and at the same time it means something else.

I have already said that the Church Slavonic language is surrounded by many different discussions and disputes. One of them is the unresolved dispute between Bulgaria and Macedonia about which dialect is the basis of the Church Slavonic language: Bulgarian or Macedonian. It seems to me that this is essentially not very important.

It is quite obvious that some South Slavic dialect known to the Thessalonica Brothers was taken as the basis. In the language of the earliest codices, both Bulgarian and Macedonian features are noted, and, moreover, interspersed with Moravisms and untranslated Greek words (like a rooster, which for some reason still remains an “alector” in the Gospel narrative) ...

But this is not the essence of the matter, because in fact this material, the material of the pre-literate tribal language, was only material, speech flesh, into which the translators, Equal-to-the-Apostles Cyril and Methodius, breathed a completely different, new, Greek spirit. They are commonly referred to as the creators of the Slavic script: in fact, it is quite fair to call them the creators of the liturgical Slavic language, this particular language, which, as far as I can imagine, has no resemblance.

And therefore, when the Cyrillic and Methodian language is called, for example, Old Bulgarian, Old Russian, Old Macedonian, such national attribution is unfair; in any case, one more word must be inserted into any of these definitions: ancient ecclesiastical Bulgarian, ancient ecclesiastical Russian, because this is a language created in the Church and for the Church. As we said, exclusively for church use.

Old Russian scribes were proud of its unique functional purity. In the treatise of Chernorizets Khrabr “On Writings”, the superiority of Slavic is argued by the fact that there is no other such pure language. It did not write letters, government decrees, secular poetry; they did not conduct idle ordinary conversations on it - they only prayed to God on it. And the Church Slavonic language has retained this property to this day.

The modern liturgical language is the fruit of a long evolution of the Old Church Slavonic language. This language is usually called synodal in philology. It acquired its final form, relative normalization, around the eighteenth century.

We can speak about almost everything in its history only approximately, because until now this history has practically not been studied by philologists, who treated these changes with a certain disdain - as a "corruption" of the original, pure language. This is typical for the nineteenth century, the real and valuable in folk culture is to consider the most ancient, original.

The evolution of the language was seen as its corruption: with the passage of time, Church Slavonic approaches Russian, becomes Russified, and thereby loses its linguistic identity. Therefore, if anything was taught to philologists and historians, then only the language of the most ancient codes, close to the time of Cyril and Methodius. However, the development of this language was by no means a degradation, it - in connection with the translations of new texts and the need to expand the theological vocabulary - was enriched, it developed, but all this remained completely unexplored.

To appreciate the scope of the changes, it is enough to put two texts of the same episode side by side: in the version of the Zograf Codex and the modern liturgical Gospel. The path from this beginning to the present state of affairs is not described by linguistics.

One can note the paradoxical nature of the evolution of the Old Church Slavonic: in principle, this development should not have happened! The initial democratic, enlightening pathos of Sts. Cyril and Methodius, who sought to bring Holy Scripture and worship closer to the cultural possibilities of the new Christian peoples, was replaced by another, conservative one, which remained leading for many centuries: it is required by all means to keep everything in the form in which it was handed down to us, any novelty is suspicious as a digression from the canon (cf. the chain built by R. Picchio for the Russian Middle Ages: Orthodoxy - legal thinking - spelling; it is enough to recall the fate of St. Maximus the Greek, who - as a dogmatic mistake - was charged with the misuse of past tenses, aorist and perfect).

Nevertheless, the Russification of Slavic took place and continues to this day, and not in the form of organized “rights” and reforms (as is known, each attempt at such a right was accompanied by sad consequences, splits and human casualties), but gradually, in the form of simplification of texts for singers.

But let us return to the relationship between Church Slavonic and Russian. These relations (as well as Church Slavonic and colloquial Bulgarian or Serbian, but I have not studied this and therefore cannot speak with confidence) are described by Boris Andreevich Uspensky as diglossia. Diglossia, not bilingualism (that is, the parallel existence of two languages).

A situation of diglossia is a situation in which there are two languages, but they are perceived by native speakers as one. In their perception, it is one and the same language in two forms (“higher” and “lower”, normalized and free), and the use of these two forms is mutually exclusive. Where one form of language is used, another is not possible, and vice versa.

It is impossible, categorically impossible to use "filthy" Russian in church services (as it was in the Middle Ages), and in the same way it is impossible to use sacred Church Slavonic in everyday life. And this second would be perceived as blasphemy. Such a situation, diglossia, is known not only in the Slavic and not only in the Christian world (cf. the resistance of some religious movements in Judaism to the everyday use of Hebrew). Usually diglossia operates where hierarchical relations are established between two languages: one language is sacred, the other is profane.

As for the intelligibility of Church Slavonic, apparently it was never completely intelligible without special preparation (and often even after it: after all, grammars and dictionaries of this language appear very late, and learning exclusively from texts does not guarantee understanding of all contexts). We have ample evidence that it was not understood in the nineteenth century.

At least the famous prayer scene in War and Peace, where Natasha Rostova understands “let us pray to the Lord for peace” as “let us pray to the Lord with the whole world”, “for heavenly peace” as “peace among angels” ...

It is not surprising that the nobility and peasants did not understand the Church Slavonic phrases, but often the clergy did not understand them either. Evidence of this is the sermons, including the sermons of illustrious figures of the Russian Church, in which the interpretation of individual verses is based on a simple misunderstanding.

For example, a sermon on the verse of the Psalm: “Take up the gates of your princes”: there follows a reasoning about why exactly “princes” should “take the gates”, based on the Russian meanings of these words, while “take” means in Slavic “raise”, and "princes" - a detail of the gate design. Examples of such profound misunderstandings can be collected, but it is not very interesting.

Moreover, one should not be surprised that the language of worship is incomprehensible to our contemporaries, who were not even taught the way our grandmothers were taught (to read texts, memorize them) and who, as a rule, did not study classical languages. After all, familiarity with the classical languages extremely helps to understand these texts: poetic inversions of hymnography, permutations of words, grammatical constructions - everything that is completely uncharacteristic of living Slavic dialects and that was brought in from Greek.

But the most difficult thing for an unprepared perception is still not the syntax, but the semantics, the meanings of words. Let's imagine a translation task equal to app. Cyril and Methodius. They needed to convey meanings for which there were no words yet!

Slavic dialects did not develop all those meanings that were necessary for the transmission of liturgical texts and texts of Scripture. Centuries of Greek thought and Hebrew literacy are invested in these meanings. The Slavic word, pre-written, did not have anything similar.

We can imagine the translation work of Cyril and Methodius in this way: they took a Greek word that coincided with some kind of Slavic in its “lower”, material meaning, and, as it were, linked these two words “for growth”. So, the Slavic "spirit" and the Greek "pneuma" are combined in their "lower" meaning - "breath". And further in the Slavic word, the whole semantic vertical, the content of the “spirit”, which was developed by Greek civilization, Greek theology, seems to grow.

It should be noted that Russian dialects have not developed this meaning. “Spirit” in dialects means only “breathing”, or “life force” (“he has no spirit” - it means “he will die soon”, there is no life force). Therefore, a researcher of folk beliefs will come across the fact that the “soul” there (contrary to the church’s idea of the body, soul and spirit) is higher than the “spirit”: the “spirit” is inherent in all living things, with the “soul” the matter is more complicated: “robbers live by the same spirit, because that their souls are already living in hell,” says the bearer of traditional beliefs based on the “first”, oral language.

The language resulting from such semantic inoculations can be called artificial in a certain sense, but in a completely different way than artificially created languages such as Esperanto: it is grown on a completely living and real verbal basis - but has moved away from this root in the direction of "heaven" meaning, that is, non-objective, conceptual, symbolic, spiritual meaning of words.

Obviously, he went further into these heavens than the Greek proper - and almost does not touch the ground. It is perceived not only as entirely allegorical, but as referring to a different reality, like an icon, which should not be compared with objective reality, natural perspective, etc.

I will allow myself to express such an assumption: this “heavenly” quality of it is very appropriate in liturgical hymnography with its contemplative, “intelligent” (in the Slavic sense, that is, immaterial) content, with its form, which is analogous to the icon-painting form (“curvature of words” , ploke) - and often the same quality does not make you feel the directness and simplicity of the word of Holy Scripture.

Another property of the Church Slavonic language is that it does not obey purely linguistic laws. Some features of its spelling and grammar are justified doctrinally rather than linguistically: for example, the different spellings of the word "angel" in the sense of "angel of God" or "spirit of evil." Or the word "word", which in the "simple" meaning of "word" is neuter, but in the meaning of "God the Word" is inflected in the masculine gender, and so on. As we have already said, the grammatical forms themselves are comprehended doctrinally.

It is in this millennial situation of diglossia that the problem of translation into Russian is rooted. It would seem, why is it so difficult or unacceptable, if these texts have already been translated into French, Finnish, English, and the translations actually work in the liturgical practice of the Orthodox Churches? Why is it so difficult with Russian?

Precisely because these two languages were perceived as one. And those means, those opportunities that Church Slavonic had at its disposal, the Russian did not develop at home. He entrusted to the Slavic language the whole realm of "high" words, the whole realm of lofty, abstract and spiritual concepts. And then, when creating the literary Russian language, the Church Slavonic dictionary was simply borrowed for its “high style”.

Since the formation of the literary Russian language, the Church Slavonic dictionary has been introduced there as the highest style of this language. We feel the difference between Church Slavonic and Russian words both stylistic and genre. Replacing Slavicisms with Russianisms gives the effect of a strong stylistic reduction.

Here is an example that my teacher, Nikita Ilyich Tolstoy, cited: he translated the phrase “the truth speaks through the mouth of an infant” entirely composed of Slavic words into Russian: it turned out: “the truth speaks through the mouth of a child.” Here, as if nothing terrible is happening, but we feel awkward, as if Pushkin’s poems “I loved you ...” were translated into youth jargon (“I’m kind of crazy from you”).

This is a very difficult problem to overcome: the Church Slavonic language is forever associated for us with a high style, with solemn eloquence; Russian - no, because he gave him this area. In addition, all Church Slavonic words, despite their real meaning, are always perceived as abstract.

“Gates” are simple gates, a household item: there are no “gates” in everyday life, “gates” are located in a different, intelligible or symbolic reality (although, contrary to everything, a football “goalkeeper” appeared from somewhere). “Eyes” are physical eyes, “eyes” are most likely non-material eyes (“eyes of the mind”) or extraordinarily beautiful spiritualized eyes.

And if you violate such a distribution and say “royal gates” or “he looked with immaterial eyes” - this will be a very bold poetic image.

For translators into Russian, this legacy of diglossia is painful. When you deal with serious lofty texts, with European poetry - Dante or Rilke - where an angel can appear, we involuntarily and automatically Slavicize. But the original does not have this, there is no this linguistic two-tier, there is one and the same word, say, "Augen", this is both "eyes" and "eyes".

We have to choose between "eyes" and "eyes", between "mouth" and "mouth", and so on. We cannot say about the mouth of an angel "mouth" and about his eyes - eyes. We are used to talking about the sublime in Russian in Slavic terms. Of course, there have been attempts to “secularise” the literary and poetic language, and one of them is Pasternak’s Gospel Poems from the Novel, where everything that happens is clearly and intentionally conveyed in Russian words and prose syntax:

And so he immersed himself in his thoughts...

But usually poets do not dare to do this. This is partly similar to how the icon image was painted in an impressionistic manner. In any case, this is an exit from the temple under the open sky of the language.

The reason for the semantic discrepancies between the Russian and Church Slavonic words most often lies in the fact that the Slavic is based on the meaning of the Greek word that the first translators associated with the Slavic morpheme, and which cannot be known to the speakers of the Slavic language if they have not received the appropriate education.

Sometimes, in this way, simple translation misunderstandings entered and forever remained in the Slavic language. So, for example, the word "food" in the sense of "delight" ("food paradise", "incorruptible food") and "food" in the meaning of "sweet" ("food paradise") arose from a mixture of two Greek words: "trophe" and "truphe" - "food" and "pleasure". Examples of this kind can be multiplied, but not all shifts are explained from the Greek substratum. Why, for example, the Greek eleison, "have mercy", in Slavic often corresponds to "cleanse"?

But, whatever the reasons for the discrepancies, such “double” words, which are included in both Russian and Church Slavonic, most often make it difficult to understand Church Slavonic texts. Here a person is sure that everything is clear to him: after all, this word - let's say, "disastrous" - he knows very well! He will look up the word "gobzuet" in the dictionary - but why find out the meaning of "destruction" there? And this word means an epidemic, a contagious disease.

While teaching, I conducted small experiments: I asked people who know these texts by heart, and even read them in temples: “What does this mean?” Not in a symbolic, not in some remote sense, but in the simplest: what is being said here?

The first reaction was usually surprise: what is there to understand? all clear. But when I nevertheless insisted that it be conveyed in other words, it often turned out that this or that turnover was understood in the exact opposite way! I repeat, I'm only talking about the literal meaning.

Here is one of my favorite examples - the word "fickle" ("astatos" in Greek): "how fickle is the greatness of thy glory." And so everyone calmly explained: nothing strange, of course, it is changeable. When I said: “But the greatness of God cannot be changed, it is always the same”, this was confusing.

In fact, the Slavic “inconstant” has nothing to do with “variability”, this is a Russian meaning. In Slavic, this means: something that cannot be "stand up", stand against. That is, "unbearable", irresistible greatness. From words of this kind, my dictionary was compiled - the first of its kind, since there have not yet been such selective dictionaries of the Church Slavonic language. This is the first attempt, and I preferred to call what I did not a “dictionary”, but “materials for a dictionary”.

Starting to collect this dictionary, I assumed that it would include several dozen words, such as the well-known “belly” or “shame” to everyone here. But it turned out that there were more than two thousand. And this is far from the end of the collection of material - it is rather the beginning.

The range of discrepancies between these Church Slavonic meanings and Russian ones can be different: sharp, up to the opposite, as in “inconstant” - or very soft and subtle, which can be overlooked. Such as, for example, in the word "quiet". "With a quiet and merciful eye." Slavic “quiet”, unlike Russian, does not mean acoustic weakness (like Russian “quiet” - quiet) and not passivity (Russian “quiet” as opposed to lively, aggressive).

Slavic "quiet" is opposed to "terrible", "threatening", "stormy". Like silence on the sea, calm, absence of a storm. "Quiet" is one in which there is no threat. And besides, the word "quiet" can convey the Greek "joyful", and not only in the prayer "Quiet Light". “God loves the quiet giver”: God loves the one who gives alms with joy.

And one more word, also very important, in which the shift in comparison with Russian seems to be not too significant - the word “warm”. Slavic “warm” is not “moderately hot”, like Russian”: it’s just “very hot”, “burning” - and hence: “zealous”. "Warm Prayer Book" - a fervent, zealous prayer book. At the same time, the habit of understanding “quiet”, “warm” in the Russian sense largely created the image of Orthodoxy.

What is Orthodoxy as a style, as an image? Images of "silence" and "warmth" will immediately come to mind - in these very, as it were, misunderstood meanings. And there are many such words, and what to do with them?

This is, I would say, a general historical, general cultural question. At some point, the historian finds out that the original meaning of one or the other has been changed, and in such a changed, distorted form, it continues for many centuries. What to do here? Insist on going back to the right start?

But this distortion itself can be fruitful, can bring interesting results. After all, it is already part of the tradition. And I would look very carefully at such things, because they constitute a tradition, a great tradition of perception of Eastern Orthodox Christianity, even if it arose from a simple linguistic misunderstanding.

This kind of misunderstanding, or understanding of Slavic words from a Russian perspective, is also shared by those who translate Orthodox worship into other languages. I looked at English, German, Italian translations - and saw that in predictable places everything is understood that way. For example, “Tenderness” (an iconographic type) will be translated everywhere as “tenderness”, “touching” (Tendresse, Tenerezza, etc.)

Whereas “tenderness” (“katanyksis”) is “contrition” or “pardon”, and not “tenderness” at all. And at the same time, the habit of inventing Russian “tenderness”, involuntary touching, and Russian “touching”, touching (Slavic: leading to contrition) to the Slavic is a habit dear to us. Clarification of meanings, on the one hand, is necessary for understanding, and, on the other hand, special delicacy is needed here so as not to cancel what is so expensive, what has already entered secular culture. What is forever remembered as a native image.

Church Slavonic, after all, is - I think it has been for many centuries - not so much a language as a text. It does not work as a language, as a structure generating real new statements. He is the statement.

The entire volume of Church Slavonic texts, all texts in Church Slavonic, is a kind of one text, one huge and beautiful statement. The smallest quotation from it is enough to evoke the whole image of church worship, its incense, fabrics, lights in the semi-darkness, melodic turns, its exclusion from linear time ... everything that is connected with the flesh of worship.

For this, not only a quotation is enough - the minimum sign of this language, some grammatical form, including an irregular form. Like Khlebnikov:

The night dorosi turn blue.

“Dorozi” – there is no such form of “road”, and yet these incorrect “dorozzi” (in fact, one letter “z” in place of “g”) immediately introduce us to the world of the Orthodox spirit, Orthodox style.

So, this language in many ways created the image of Russian Orthodoxy, “quiet” and “warm”. You can talk for a long time about how he influenced Russian culture in general. What does this habit of bilingualism, understood as monolingualism, mean and what entails, this very complex psychological attitude. What does it mean and what does the centuries-old habit of accepting the sacred word, knowing it by heart and not being hindered by its "darkness", "half-understanding" mean?

It is not customary to require complete distinctness from such a word: what is expected of it is power. A sacred word is a powerful word. And the Russian everyday word, as it were, obviously does not possess this power. It can acquire it in poetry - but here, as they say, "a person must burn", a personal genius must act.

The Church Slavonic word possesses this power, as it were, by itself, without its own Pushkin or Blok. Why, where? we are unlikely to answer this question. I heard similar impressions from Catholics who told me quite recently how some exorcist read prayers in Latin, and they acted: as soon as he pronounced them translated into French, they ceased to act.

This is how the Church Slavonic language is perceived: as a strong, domineering language. Not the language, actually, but the text, as I said. Of course, new texts were created - compiled - on it, but it can hardly be called an essay. This is a mosaic of fragments of already existing texts, compiled in a new order according to the laws of the genre: akathist, canon...

It is impossible to compose a new work in the Church Slavonic language - new according to our concepts of the new. The power of the Church Slavonic word is close to magical - and it is preserved in any quotation - and in one where nothing actually church, liturgical is supposed. As, for example, in "Poems to the Block" by Marina Tsvetaeva:

You will see the evening light.

You go to the sunset

And the blizzard covers the trail.

Past my windows - impassive -

You will pass in the snowy silence,

God's righteous man is my beautiful,

Quiet light of my soul.

Called up by several inlays taken from it, the prayer "Quiet Light" in these verses plays with all its properties of a sacred, beautiful, mysterious word.

I believe that some properties of Russian poetry are connected with this popular habit of imperious and conceptually incomprehensible sacred language. As far as I can judge, Russian poetry in the nineteenth, and even more so, in the twentieth century, much more easily than other European traditions, allowed itself the fantasy of a word, displacements of its dictionary meaning, strange combinations of words that do not require any final "prosaic" understanding :

And breathes the mystery of marriage

In a simple combination of words,

as the young Mandelstam wrote. Perhaps this will surprise someone, but Alexander Blok seems to me the most direct heir to the Church Slavonic language, who never equipped his speech with rich Slavonicisms, as Vyacheslav Ivanov did, but his language itself carries the magical non-objective power of the Church Slavonic word, which inspires without explaining:

This strand, so golden,

Is it not from the old fire?

Dear, godless, empty,

Unforgettable - forgive me!

There are no quotations here, but everyone recognizes in this triple step of epithets the rhythm and power of prayer.

Much can be said about the fate of Church Slavonic in secular culture. I will dwell, perhaps, only on one more, very significant episode: on the poetry of Nekrasov and the people's will. This is where the special imperious persuasive power of Slavic revolutions played its role!

The participants in this movement recall that if they had only read the articles of the socialists, written in the "Western" "scientific" language, like Belinsky's, it would not have affected them at all. But Nekrasov, who unexpectedly introduced the Church Slavonic language in an unusually rich, generous manner, found a fascinating word for the ideology of populism. A long, compound Slavic word:

From the jubilant, idle chatters,

Blood-stained hands

Take me to the camp of the perishing

For the great work of love.

The liturgical language, with its key words - love, sacrifice, path - turned out to be irresistibly convincing for the youth of that time. He interpreted their work for them as a "holy sacrifice", as a continuation of the liturgy.

I will only mention another pseudomorphosis of Church Slavonic - the official language of Stalinist propaganda, which, according to linguists, consisted of 80% of Slavicisms (this is the composition of the old edition of Mikhalkov's "Hymn of the Soviet Union").

And finally, the last topic for today: the literary Russian language. His position was very difficult. “Above” was the sacred Church Slavonic language, coinciding with it in the zone of sublime, abstract words. On the other hand, "from below" he was washed by a sea of living dialects, in relation to which he himself resembled Church Slavonic.

All Russian writers, right down to Solzhenitsyn, felt this: the Russian literary language seems to be incorporeal, abstract, impersonal - in comparison with the bright, material word of living folk dialects. Until a certain time, the Russian writer had three possibilities, three registers: a neutral literary language, high Church Slavonic and a lively, playful word of dialects. The normative Soviet writer no longer had either Church Slavonic or literary: only the word of dialects could save the situation.

Literary Russian language, about which the already mentioned Isachenko once wrote a scandalous article (in French) “Is the literary Russian language Russian in origin?” And he answered: “No, this is not the Russian language, this is the Church Slavonic language: it is cast in the same way in the image of Church Slavonic, as Church Slavonic is in the image of Greek.”

I omit his arguments, but in fact, literary Russian differs from dialects in the same way as - with all mutatis mutandis - Church Slavonic differed from them. It is in many ways a different language. By the way, in the documents of the Council of 1917, published by Fr. Nikolai Balashov, I came across a wonderful note by one of the participants in the discussion about the liturgical language, concerning the “incomprehensibility” of Church Slavonic.

The author (I, unfortunately, do not remember his name) notes that the language of contemporary fiction and journalism is no less incomprehensible to the people than Church Slavonic. And in fact, the literary language is just as incomprehensible to a native speaker of Russian, if he has not received a certain education. These are “incomprehensible”, “foreign” words (not only barbarisms, which the literary language, unlike conservative dialects, easily absorbs into itself - but also proper Russian words with a different semantics that does not arise directly from the language itself, from the dialects themselves).

Yes, the vocabulary of the literary language in its vast majority seems to people who have not received a certain education, in grammar - Russian, in meaning - foreign. I think that everyone has had to deal with this, talking to a person who can ask again: what do we think, what you said? The literary language is, as it were, foreign to them, and thus it bears the properties of the Church Slavonic language, its non-objectiveness, its supernaturalness.

That, in fact, is all that I could tell you today about the Church Slavonic language in Russian culture, although this is an endless topic. This is a conversation about the great treasure of our culture, losing which we will lose touch not only with Church Slavonic texts, but also with the secular Russian literature of the last three centuries. And this is a conversation about a treasure that from the very beginning carried a certain danger in itself: a strong, beautiful, inspiring, but not interpreting, not interpreted word.

Have you read the article Church Slavonic: words for meanings. Read also.

Under the name of the Church Slavonic language or the Old Church Slavonic language, it is customary to understand the language into which in the 9th century. a translation of the Holy Scriptures and liturgical books was made by the first teachers of the Slavs, St. Cyril and Methodius. The term Church Slavonic in itself is inaccurate, because it can equally refer both to the later types of this language used in Orthodox worship among various Slavs and Romanians, and to the language of such ancient monuments as the Zograf Gospel, etc. The definition of "ancient -Church Slavonic language" language also adds little to the accuracy, because it can refer both to the language of the Ostromir Gospel, and to the language of the Zograf Gospel or Savina's book. The term "Old Slavonic" is even less precise and can mean any old Slavic language: Russian, Polish, Czech, etc. Therefore, many scholars prefer the term "Old Bulgarian" language.

Church Slavonic, as a literary and liturgical language, received in the 9th century. widespread use among all Slavic peoples baptized by the first teachers or their students: Bulgarians, Serbs, Croats, Czechs, Moravans, Russians, perhaps even Poles and Slovenes. It has been preserved in a number of monuments of Church Slavonic writing, hardly dating back further than the 11th century. and in most cases in more or less close connection with the above-mentioned translation, which has not come down to us.

Church Slavonic has never been a spoken language. As a book, it was opposed to living national languages. As a literary language, it was a standardized language, and the standard was determined not only by the place where the text was rewritten, but also by the nature and purpose of the text itself. Elements of lively colloquial (Russian, Serbian, Bulgarian) could penetrate Church Slavonic texts in one quantity or another. The norm of each specific text was determined by the relationship between the elements of the book and the living spoken language. The more important the text was in the eyes of a medieval Christian scribe, the more archaic and stricter the language norm. Elements of spoken language almost did not penetrate into liturgical texts. The scribes followed tradition and focused on the most ancient texts. In parallel with the texts, there was also business writing and private correspondence. The language of business and private documents combines elements of the living national language (Russian, Serbian, Bulgarian, etc.) and separate Church Slavonic forms.

The active interaction of book cultures and the migration of manuscripts led to the fact that the same text was copied and read in different editions. By the XIV century. came the understanding that the texts contain errors. The existence of different editions did not allow us to decide which text is older, and therefore better. At the same time, the traditions of other peoples seemed more perfect. If the South Slavic scribes were guided by Russian manuscripts, then the Russian scribes, on the contrary, believed that the South Slavic tradition was more authoritative, since it was the South Slavs who preserved the features of the ancient language. They valued Bulgarian and Serbian manuscripts and imitated their orthography.

Along with the spelling norms, the first grammars came from the southern Slavs. The first grammar of the Church Slavonic language, in the modern sense of the word, is the grammar of Lawrence Zizanias (1596). In 1619, the Church Slavonic grammar of Melety Smotrytsky appeared, which determined the later language norm. In their work, the scribes sought to correct the language and text of the books being copied. At the same time, the idea of what a correct text is has changed over time. Therefore, in different eras, books were corrected either from manuscripts that the editors considered ancient, or from books brought from other Slavic regions, or from Greek originals. As a result of the constant correction of liturgical books, the Church Slavonic language acquired its modern look. Basically, this process was completed at the end of the 17th century, when, at the initiative of Patriarch Nikon, the liturgical books were corrected. Since Russia supplied other Slavic countries with liturgical books, the post-Nikonian appearance of the Church Slavonic language became the general norm for all Orthodox Slavs.

In Russia, Church Slavonic was the language of church and culture until the 18th century. After the emergence of a new type of Russian literary language, Church Slavonic remains only the language of Orthodox worship. The corpus of Church Slavonic texts is constantly replenished: new church services, akathists and prayers are being compiled.

Church Slavonic and Russian

Church Slavonic played an important role in the development of the Russian literary language. The official adoption of Christianity by Kievan Rus (988) led to the recognition of the Cyrillic alphabet as the only alphabet approved by secular and ecclesiastical authorities. Therefore, Russian people learned to read and write from books written in Church Slavonic. In the same language, with the addition of some Old Russian elements, they began to write ecclesiastical literary works. In the future, Church Slavonic elements penetrate into fiction, journalism, and even state acts.

Church Slavonic until the 17th century. was used by Russians as one of the varieties of the Russian literary language. Since the 18th century, when the Russian literary language was mainly based on living speech, Old Slavonic elements began to be used as a stylistic tool in poetry and journalism.

The modern Russian literary language contains a significant number of different elements of the Church Slavonic language, which have undergone certain changes in one way or another in the history of the development of the Russian language. So many words have entered the Russian language from the Church Slavonic language and they are used so often that some of them, having lost their book color, have penetrated into the spoken language, and the words parallel to them of primordially Russian origin have fallen into disuse.

All this shows how organically the Church Slavonic elements have grown into the Russian language. This is why it is impossible to thoroughly study the modern Russian language without knowing the Church Slavonic language, and this is why many phenomena of modern grammar become understandable only in the light of studying the history of the language. Acquaintance with the Church Slavonic language makes it possible to see how the linguistic facts reflect the development of thinking, the movement from the concrete to the abstract, i.e. to reflect the connections and patterns of the surrounding world. Church Slavonic helps to understand the modern Russian language deeper and more fully.

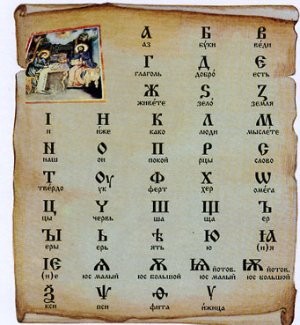

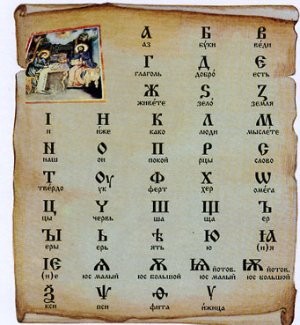

Alphabet of the Church Slavonic language

| az | BUT | i | Y | firmly | T | er (s) | S | |||||||||||

| beeches | B | kako | To | uk | At | er | b | |||||||||||

| lead | AT | people | L | fert | F | yat | E | |||||||||||

| verb | G | think | M | dick | X | Yu | YU | |||||||||||

| good | D | our | H | from | from | I | I | |||||||||||

| there is |

Church Slavonic language, a medieval literary language that has survived to our time as the language of worship. It goes back to the Old Church Slavonic language created by Cyril and Methodius on the basis of South Slavic dialects. The most ancient Slavic literary language spread first among the Western Slavs (Moravia), then among the southern Slavs (Bulgaria), and eventually becomes the common literary language of the Orthodox Slavs. This language has also become widespread in Wallachia and some areas of Croatia and the Czech Republic. Thus, from the very beginning, Church Slavonic was the language of the church and culture, and not of any particular people.

Church Slavonic was the literary (bookish) language of the peoples inhabiting a vast territory. Since it was, first of all, the language of church culture, the same texts were read and copied throughout this territory. Monuments of the Church Slavonic language were influenced by local dialects (this was most strongly reflected in spelling), but the structure of the language did not change. It is customary to talk about editions (regional variants) of the Church Slavonic language - Russian, Bulgarian, Serbian, etc.

Church Slavonic has never been a spoken language. As a book, it was opposed to living national languages. As a literary language, it was a standardized language, and the standard was determined not only by the place where the text was rewritten, but also by the nature and purpose of the text itself. Elements of lively colloquial (Russian, Serbian, Bulgarian) could penetrate Church Slavonic texts in one quantity or another. The norm of each specific text was determined by the relationship between the elements of the book and the living spoken language. The more important the text was in the eyes of a medieval Christian scribe, the more archaic and stricter the language norm. Elements of spoken language almost did not penetrate into liturgical texts. The scribes followed tradition and focused on the most ancient texts. In parallel with the texts, there was also business writing and private correspondence. The language of business and private documents combines elements of the living national language (Russian, Serbian, Bulgarian, etc.) and separate Church Slavonic forms.

The active interaction of book cultures and the migration of manuscripts led to the fact that the same text was copied and read in different editions. By the 14th century came the understanding that the texts contain errors. The existence of different editions did not allow us to decide which text is older, and therefore better. At the same time, the traditions of other peoples seemed more perfect. If the South Slavic scribes were guided by Russian manuscripts, then the Russian scribes, on the contrary, believed that the South Slavic tradition was more authoritative, since it was the South Slavs who preserved the features of the ancient language. They valued Bulgarian and Serbian manuscripts and imitated their orthography.

Along with the spelling norms, the first grammars came from the southern Slavs. The first grammar of the Church Slavonic language, in the modern sense of the word, is the grammar of Lawrence Zizanias (1596). In 1619, the Church Slavonic grammar of Melety Smotrytsky appeared, which determined the later language norm. In their work, the scribes sought to correct the language and text of the books being copied. At the same time, the idea of what a correct text is has changed over time. Therefore, in different eras, books were corrected either from manuscripts that the editors considered ancient, or from books brought from other Slavic regions, or from Greek originals. As a result of the constant correction of liturgical books, the Church Slavonic language acquired its modern look. Basically, this process was completed at the end of the 17th century, when, on the initiative of Patriarch Nikon, the liturgical books were corrected. Since Russia supplied other Slavic countries with liturgical books, the post-Nikonian appearance of the Church Slavonic language became the general norm for all Orthodox Slavs.

In Russia, Church Slavonic was the language of church and culture until the 18th century. After the emergence of a new type of Russian literary language, Church Slavonic remains only the language of Orthodox worship. The corpus of Church Slavonic texts is constantly replenished: new church services, akathists and prayers are being compiled.

Being the direct heir of the Old Church Slavonic language, Church Slavonic has retained many archaic features of the morphological and syntactic structure to this day. It is characterized by four types of noun declension, has four past tense verbs and special nominative participle forms. The syntax preserves the tracing Greek turns (dative independent, double accusative, etc.). The spelling of the Church Slavonic language underwent the greatest changes, the final form of which was formed as a result of the "book right" of the 17th century.