FORMATION OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE. DEVELOPMENT OF THE STATES OF EUROPE AND ASIA

CHAPTER 1=-

EARLY ROMAN EMPIRE

RULE OF AUGUST. PRINCIPATE

MUNICIPAL LIFE IN ITALY

PROVINCIAL LIFE

RESULTS OF THE REIGN OF EMPEROR AUGUST

THE PERSON OF OCTAVIAN AUGUST

CULTURE DURING THE CHANGE OF AGES

ROMAN EMPIRE IN I V. N. E.

UPRISING OF THE GERMAN AND PANNONIAN LEGIONS

POLITICS YULIEV KLAUDIEV

THE LIFE OF THE EMPIRE IN THE YEARS OF THE EMPERORS OF THE JULIAN-CLAUDIAN DYNASTY

EMPIRE CULTURE OF THE PRINCIPATE PERIOD

CHAPTER 2=-

THE ROMAN EMPIRE IN THE PERIOD OF THE HIGHEST POWER

STRENGTHENING OF IMPERIAL POWER

THE BOARD OF THE ANTONINS.

LIFE OF THE EMPIRE IN THE SECOND HALF OF THE I CENTURY - THE BEGINNING OF THE II CENTURY

WESTERN AND EASTERN PROVINCES IN THE SECOND HALF OF THE 1st C. AND IN THE 2nd C.E.

ECONOMIC LIFE OF THE EMPIRE IN THE SECOND HALF I B. - II V. AD

CULTURE

THE BIRTH OF CHRISTIANITY

CHAPTER 3=-

PARTHIA IN THE FIGHT WITH ROME

ARMENIA IN THE FIGHT AGAINST ROME

COLCHIS UNDER ROMAN EMPIRE

NORTHERN BLACK SEA REGION

RELATIONS OF THE GERMANS WITH THE ROMAN EMPIRE

KINGDOM OF DECEBALS

OLD SLAVIC TRIBES

LATE ROMAN EMPIRE

CHAPTER 1=-

ROMAN EMPIRE III CENTURY A.D.

CIVIL WAR 193 - 197 N.E.

THE INNER LIFE OF THE EMPIRE

SEPTIMIUS NORTH

SEVER DYNASTY

POLITICAL CRISIS OF THE EMPIRE OF THE III CENTURY AD

RESTORATION OF THE UNITY OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE

ESTABLISHING DOMINATE. EMPEROR DIOCLETIAN

CULTURE OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE OF THE III CENTURY

CHAPTER 2=-

STATES OF ASIA AND EUROPE IN THE III CENTURY AD

MIDDLE ASIA

SASANID IRAN

KARTLI AND ALBANIA

NORTHERN BLACK SEA REGION

NOMADERS OF THE ASIAN STEPPES

TRIBES OF EUROPE

CHAPTER 3=-

DIVISION OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE EMPEROR CONSTANTINE

DECLINE OF CITIES. BARPARIZATION OF THE ARMY

CONSTANTIUS AND JULIAN

DIVISION OF THE EMPIRE INTO WESTERN AND EASTERN

FALL OF THE WESTERN ROMAN EMPIRE

WRITTEN SOURCES FOR THE STUDY OF THE HISTORY OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE

ANCIENT CHRISTIAN LITERATURE

*PART I*

FORMATION OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE. DEVELOPMENT OF THE STATES OF EUROPE AND ASIA

-=CHAPTER 1=-

EARLY ROMAN EMPIRE

The history of ancient Rome is usually divided into two stages. The first begins its countdown from the conquest of the Apennine Peninsula by Rome and the formation of the Roman-Italian alliance (VI - III centuries BC). It includes the creation of the Roman Mediterranean power (III - I centuries BC), which is usually called the Roman Republic.

The second stage in the history of ancient Rome begins with the fall of the republican system in the thirties of the 1st century. BC e. and the formation of the Roman Empire.

In this volume of the encyclopedia, we will consider the second stage in the history of Ancient Rome.

The Roman Empire did not arise in a vacuum. The ground for education was created by Gaius Julius Caesar (born in 100 BC), who managed to actually erect a military monarchy within the framework of the republican system.

During the period of incessant civil wars and internal strife, which literally tore the state apart, he managed, “by defeating his opponents, not only to keep the gigantic state from collapse, but also to strengthen its borders.

Here is a quote from the largest German historian, philologist and lawyer Theodor Mommsen (1817 - 1903), whose scientific work "History of Rome" has worldwide fame. In it, he gave a brilliant analysis of the events that took place in the most important period of European history and for the first time formulated fundamental conclusions. Even today they amaze with their depth, accuracy and versatility:

“Here is the briefest sketch of what Caesar did. A short time was given to him by fate, but this extraordinary man with brilliant talents combined unprecedented energy in work and worked uninterruptedly, tirelessly, as if he had no tomorrow. Two hundred years before his time, social and economic difficulties had reached their extreme limit in Rome and threatened to destroy the people. Then Rome was saved by the fact that it united all of Italy under its rule and smoothed out in a broader field, internal contradictions disappeared, from which the small community suffered unbearably. Now again in the Roman state the social question has matured to the point of crisis. The state was languishing in internal turmoil and it seemed that there was no way out of them. But the genius of Caesar found a way of salvation: merging into one huge whole all the countries around the Mediterranean Sea, Caesar directed them to internal unification and on this huge, once seemingly boundless field, that struggle between the rich and the poor, which did not find a solution within Italy alone. could resolve naturally and without difficulty.

The history of the Hellenes and Latins ended with the activities of Caesar. After the Greeks and Italics separated, one of these nationalities discovered marvelous talents in the field of individual creativity, in the field of culture. The other developed the largest and most powerful state body. In its area, each of these tribes had reached the highest possible limit for mankind and, due to the one-sidedness of its development, was already declining. At this time, Caesar appeared. He merged into one nationality, which created a state, but had no culture, with a nationality, which had a higher culture, but did not have a state. The two most gifted tribes of the ancient world have now come together again, in their union they have drawn new spiritual forces, have worthily filled the entire vast sphere of human activity, and by joint work have created the basis on which human genius can work, it seems, without limit. No other paths for human development have been found. There is an infinite amount of work in the new field, and all mankind is still working on it in the same spirit and direction as Caesar, who, in the minds of all peoples, remains the only emperor, the personification of power.

The beginning of the second period of the Roman Empire, namely the formation of the Roman Empire, is associated with the name of Gaius Octavius, who was declared in the will of Gaius Julius Caesar as the heir to his property and was his great-nephew. At the time of the assassination of Caesar, Gaius Octavius was in Apollonia Illyria.

Having learned about the criminal conspiracy, as a result of which his great relative died, he immediately arrived in Rome and demanded from Mark Antony, who at that time led the Caesarians, to transfer to him, according to Caesar's will, large sums of money, which by this time Antony had managed to appropriate to himself .

Antony refused him and Gaius Octavius began to seek support from Mark Tullius Cicero, who at that time was the leader of the Republicans in the Senate.

Cicero, considering this a great success for himself and trying to weaken the Caesarians, passed a resolution through the Senate, by which Gaius Octavius was recognized as the adopted son and legitimate heir of Gaius Julius Caesar. From that moment on, Octavius became known as Gaius Julius Caesar Octavian.

Having become the heir to huge wealth and fulfilling the will of Gaius Julius Caesar, Octavian distributed to the poorest citizens of Rome the amount of money that Caesar bequeathed to them, and this gained popularity among the plebs and veterans.

Seeing that his influence in the city was weakening every day, Mark Antony left for Cisalpine Gaul. After his departure, the senate declared Antony an enemy of the Republic. Cicero, who was known as an unsurpassed orator, began to make speeches against him, to which he himself gave the name "Philippi". But he perfectly understood that things could not go further than these speeches, since in fact the Senate could not fight against Mark Antony - he had no troops.

When the Roman civil community subjugated most of the known world, its state structure ceased to correspond to reality. It was possible to restore the balance in the administration of the provinces only under the conditions of the empire. The idea of autocracy took shape in Julius Caesar and entrenched in the state under Octavian Augustus.

Rise of the Roman Empire

After the death of Julius Caesar, a civil war broke out in the republic between Octavian Augustus and Mark Antony. The first, in addition, killed the son and heir of Caesar - Caesarion, eliminating the opportunity to challenge his right to power.

Defeating Antony at the Battle of Actium, Octavian became the sole ruler of Rome, taking the title of emperor and turning the republic into an empire in 27 BC. Although the power structure was changed, the flag of the new country did not change - it remained an eagle depicted on a red background.

Rome's transition from republic to empire was not an overnight process. The history of the Roman Empire is usually divided into two periods - before and after Diocletian. During the first period, the emperor was elected for life and next to him was the Senate, while during the second period the emperor had absolute power.

Diocletian, on the other hand, changed the procedure for obtaining power, passing it on by inheritance and expanding the functions of the emperor, and Constantine gave it a divine character, religiously substantiating its legitimacy.

TOP 4 articleswho read along with this

Roman Empire at its height

During the years of the existence of the Roman Empire, many wars were fought and a huge number of territories were annexed. In domestic policy, the activities of the first emperors were aimed at the Romanization of the conquered lands, at appeasing the peoples. In foreign policy - to protect and expand borders.

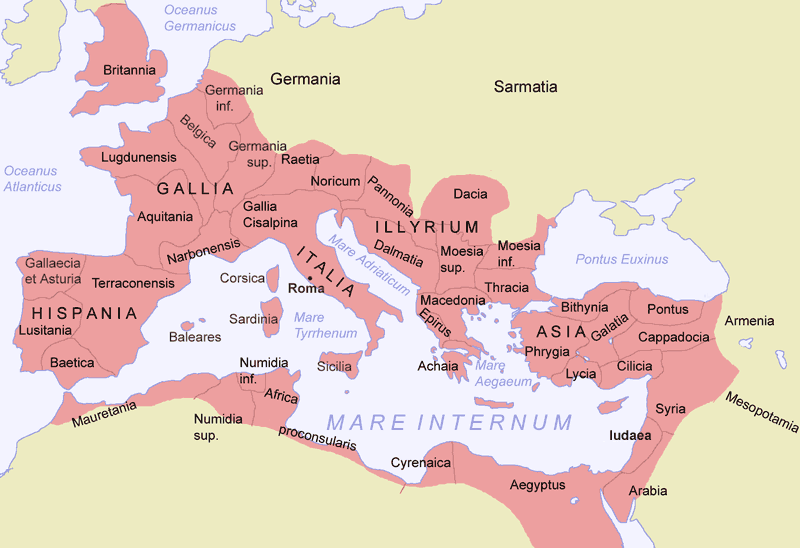

Rice. 2. The Roman Empire under Trajan.

In order to protect against the raids of the barbarians, the Romans built fortified ramparts, called by the names of the emperors under whom they were built. Thus, the Lower and Upper Trajan's ramparts in Bessarabia and Romania are known, as well as the 117-kilometer Hadrian's Wall in Britain, which has survived to this day.

August made a special contribution to the development of the regions of the empire. He expanded the road network of the empire, established strict supervision of the governors, conquered the Danubian tribes and waged a successful struggle with the Germans, securing the northern borders.

Under the Flavian dynasty, Palestine was finally conquered, the uprisings of the Gauls and Germans were suppressed, and the Romanization of Britain was completed.

The empire reached its highest territorial scope under the emperor Trajan (98-117). The Danubian lands underwent Romanization, the Dacians were conquered, and a struggle was waged against the Parthians. Adrian, who replaced him, on the contrary, was engaged in purely internal affairs of the country. He constantly visited the provinces, improved the work of the bureaucracy, built new roads.

With the death of Emperor Commodus (192), the period of "soldier" emperors begins. The legionnaires of Rome, at their whim, overthrew and installed new rulers, which caused the growth of the influence of the provinces over the center. The “epoch of 30 tyrants” is coming, which resulted in a terrible turmoil. Only by 270 did Aurelius manage to establish the unity of the empire and repel the attacks of external enemies.

Emperor Diocletian (284-305) understood the need for urgent reforms. Thanks to him, a true monarchy was established, and a system of dividing the empire into four parts under the control of four rulers was also introduced.

This need was justified by the fact that, due to their huge size, communications in the empire were very stretched and news of barbarian invasions reached the capital with a strong delay, and in the eastern regions of the empire, the popular language was not Latin, but Greek and in money circulation instead of denarius drachma went.

With this reform, the integrity of the empire was strengthened. His successor, Constantine, officially entered into an alliance with the Christians, making them his support. Perhaps that is why the political center of the empire was moved to the east - to Constantinople.

Decline of an empire

In 364, the structure of the division of the Roman Empire into administrative parts was changed. Valentinian I and Valens divided the state into two parts - eastern and western. This division corresponded to the basic conditions of historical life. Romanism triumphed in the West, Hellenism triumphed in the East. The main task of the western part of the empire was to contain the advancing barbarian tribes, using not only weapons, but also diplomacy. Roman society became a camp where every stratum of society served this purpose. Mercenaries began to form the basis of the empire's army more and more. Barbarians in the service of Rome protected it from other barbarians. In the East, everything was more or less calm and Constantinople was engaged in domestic politics, strengthening its power and strength in the region. The empire united several more times under the rule of one emperor, but these were only temporary successes.

Rice. 3. Division of the Roman Empire in 395.

Theodosius I is the last emperor who united the two parts of the empire together. In 395, dying, he divided the country between his sons Honorius and Arcadius, giving the eastern lands to the latter. After that, no one will succeed in uniting the two parts of the vast empire again.

What have we learned?

How long did the Roman Empire last? Speaking briefly about the beginning and end of the Roman Empire, we can say that it was 422 years. It inspired fear in the barbarians from the moment of its formation and beckoned with its riches when it collapsed. The empire was so large and technologically advanced that we still use the fruits of Roman culture.

Topic quiz

Report Evaluation

Average rating: 4.5. Total ratings received: 182.

Octavian Augustus, as a person and as a statesman, caused conflicting opinions even in ancient times. During his lifetime and in the first years after his death, a pronounced apologetic trend arose in Roman historiography, and even more widely in Roman literature. It was presented by such historians as Nicholas of Damascus, Velleius Paterculus, in a more moderate form - by Titus Livius and Dio Cassius, the latter being usually considered the main source on the era of Augustus. There was, undoubtedly, another direction - a critical, oppositional one, whose representatives defended the views and slogans of the "last Republicans", but practically nothing has come down to us from their works. Later historians, starting with Tacitus, usually give an ambivalent assessment, but it turns out to be quite detailed and meaningful.

For example, Tacitus himself at the beginning of the Annals, shortly after he makes his famous statement about his lack of "anger and passion" (sine ira et studio), gives a very peculiar characterization of Octavian Augustus. It is based on the opinions and sayings of the Romans shortly after the death of the aged emperor, with positive statements grouped first and then negative ones. The first includes the listing of honorary positions and titles of Augustus, emphasizing his love for his father, i.e., Julius Caesar, and justifying this love of initiative in the civil war, then pointing to the new political system he created without royal power and without dictatorship, to expand the state and ensuring its security, the adornment of Rome and, finally, the fact that violence was used only in rare cases and in order to preserve peace and tranquility for the majority.

However, then opposite statements are given, according to which love for the father was only a pretext for the struggle for power, allusions are made to Octavian's involvement in the death of Hirtius and Pansa, it is said about the capture of the first consul by force and about the conversion of the troops received to fight Antony against himself. states. Of course, the actions of Octavian during the proscriptions and the division of the Italian lands are condemned. Then there are accusations of deceit and deceit, abuse of executions, insufficient reverence for the gods, and even gossip and gossip about family affairs and life, so typical of those times. The most remarkable thing in this dual characterization is the fact that Tacitus himself in no way betrays his own attitude towards the personality of Augustus.

With the most complete and detailed description, we, as expected, come across in the biography of Octavian Augustus, written by Suetonius. But it also bears the stamp of duality and contradictions.

While we are talking about Octavian-triumvir, i.e., about the period of his struggle for power, he is portrayed as an extremely cruel person (reprisal against prisoners after the capture of Perusia, behavior during proscriptions, etc.), but upon reaching power, he turns out to be merciful and a generous and even kind-hearted judge. If at the beginning of the biography Mark Antony's mockery of his cowardice is mentioned, then later examples are given that refute such suspicions. It is said with praise that he categorically forbade the erection of temples in his honor in Rome (only in the provinces, and even then with a double dedication: to him and Rome), that he did not pay serious attention to impudent attacks and anonymous letters, that he held the foundations of justice, and as many as four chapters of the biography - from 57 to 60 inclusive - are devoted to describing the voluntary manifestations of the "nationwide" love for Augustus.

With this, Suetonius completes that part of the biography that is devoted to the characterization of Octavian Augustus as a military and political figure, and proceeds to describe his personal qualities. He pays great attention to them, down to describing the appearance of Augustus or his unpretentiousness in food. He specifically dwells on his interest in the "noble sciences", in eloquence, as well as on a good knowledge of Greek and Latin authors. The biography ends with a description of the death of Augustus and his funeral, and - and this, of course, is a brilliant final touch on the general characterization - it is told how the dying emperor turned to his relatives with the following question: did they think he played the comedy of life well, and demanded , in case of an affirmative answer, applause.

These are the most typical estimates and characteristics of antiquity itself. As for the new time, we can say that against the background of the brilliant and always impressive personality of Caesar, the figure of Augustus seemed pale and even insignificant. In any case, he did not inspire sympathy with the new historians and did not enjoy their recognition.

Even the French enlighteners, for whom Augustus was a usurper and strangler of the republic, spoke sharply negatively about him. Thus, Voltaire spoke of a "monster", of "a man without shame, without faith and honor"; Montesquieu also considered him a bloodthirsty tyrant who established "long-term slavery" for his subjects. In the once famous work of Gibbon, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Augustus is characterized by the following words: “A cold mind, an insensitive heart and a cowardly character made him, when he was nineteen years old, put on a mask of hypocrisy, which he subsequently never took off ". Hardthausen, in his three-volume work, compares Augustus to Napoleon III. Perhaps, of the new historians, Augustus Ferrero is most positively assessed, opposing him to the "brilliant loser" Caesar. But he also writes about him in such terms: “This smart egoist, who had neither vanity nor ambition, this hypochondriac, who was afraid of sudden unrest, this thirty-six-year-old man, prematurely aged, this cautious counter, cold and timid, did not make illusions for himself” .

The Soviet researcher of the principate of Augustus, N. A. Mashkin, also turns out to have a very low opinion of the personal qualities and talents of Caesar's successor. He says: “Although Augustus did much more to establish monarchical power than his adoptive father, yet we cannot compare him with Julius Caesar. In terms of ability, he was inferior not only to Caesar, but also to many of his associates. He advanced not because of his abilities, but because he took the name of Caesar and, together with his associates, correctly assessed the situation and outlined ways to overcome difficulties. August was able to see his shortcomings and knew how to choose and attract people.”

So, a hypocrite and a coward, an egoist and a hypochondriac, an insidious and cruel tyrant, besides a man of very average abilities - such or almost such an image is presented to us by new historiography. A rare, or rather exceptional, case of a huge discrepancy, a gap between the insignificance of the doer and the greatness of the deed! Is it really?

We are not at all going to create an apologetic image of Octavian Augustus. But we would like to emphasize one - and, from our point of view, the most characteristic - feature of his personality, in comparison with which all the rest can be considered, as it were, secondary and subordinate. Octavian Augustus was a born politician, a politician par excellence, a politician from head to toe, and as such he represents an exceptional, perhaps even the only phenomenon, at least in ancient history.

Deciding at the age of 19, and against the advice of his relatives and friends, to inherit from Caesar not only his name, but also his special position in the state, he has since known “the power of only one thought”, and this “thought” he consistently and without any hesitation, subordinates all his other intentions and actions. Before him all the time there is only one goal - to achieve a leading position in Rome, and to fulfill this vital task he directs all physical and spiritual forces. When we talk about Augustus and have in mind his political career, the idea of a clearly defined and defined goal does not at all look like a teleological exaggeration. On the contrary, in all his actions - both large and small - the constantly tangible presence of far-sighted calculation is striking. Moreover, this is not only a dry and sober, so to speak, “mundane” calculation, no, it is often inspired by brilliant intuition - in essence, without intuition, and therefore, without risk, there is not and cannot be big politics, a policy of “far sight”.

The political genius of Augustus is almost terrifying. Tactical calculation and strategic foresight are combined in it so naturally and so perfectly that often a pre-calculated act looks like an intuitively made decision, and an obviously, at first glance, intuitive action suddenly turns into a sober calculation. As a result, not a single major mistake, not a single blunder throughout the entire political career. An example in history, in our opinion, is absolutely unprecedented! On the other hand, the bearer of these qualities was forced to pay with the loss of purely human qualities - the politician in him ousted, destroyed the person; it was no longer a man, but an almost irreproachable political mechanism, a robot.

We would now like to confirm with some specific examples the idea that the political genius of Augustus was able to somehow transform, use, in any case, put all the other properties and features of his personality at his service. Is it true that he did not have military talents, was weak, and besides, also an unsuccessful commander? Yes, he was, but this shortcoming of his, this weakness, he managed to turn into strength, fighting, as a rule, with proxy or when he conducted military operations personally, showing extreme caution, in accordance with his favorite sayings: “Hurry without haste” or "A cautious commander is better than a reckless one."

Is it true that he was a treacherous and cruel man, a deceiver, a traitor to his friends? Nobody knows this, because it is not known who he really was, what were his human qualities. But something else is well known: when need, he was cruel, and when need was different - kind and merciful. All human feelings in him were also subject to political calculation (or intuition). The pinnacle of such a calculation can be considered the fact, testified by his biographer, that with his own wife Livia, in some important cases, he spoke according to a pre-compiled summary, and the pinnacle of intuition is entering into an alliance with Antony after he was defeated in the Mutinskaya war.

After all, this step led to the creation of the second triumvirate, to joint actions under Philippi, and in general to everything that was the main content of Roman history until the triumvirate itself collapsed, and which, of course, in no way succumbed to any preliminary calculation.

All this taken together was the main reason for the contradictory characteristics of ancient - and, perhaps, modern - historians. In addition, we should not forget that Augustus ruled the state, according to the calculations of the ancients themselves, for more than half a century: 12 years together with Antony and Lepidus and 44 years as autocrat. Therefore, his image both as a person and as a political figure should not be presented statically, although at any given moment he is quite complex and contradictory, but in a certain development. The political aspect of the image of Octavian is extremely interesting because in his political activity, if it is considered in development and throughout, all the forms of government known at that time are embodied, as it were, both correct and “perverted”: dictatorship and tyranny, aristocracy, democracy and oligarchy and, finally, the republic and the monarchy. And a peculiar fusion of all these forms and elements gave rise to that completely new, perhaps the only political system in history, which received the name principate. As for the private, or "human" aspect of the image of Octavian, then, most likely, this is the image of an actor who continuously and tirelessly performs a certain role and "wins" in it so much that it has become life itself for him, as he directly and said in the above dying words.

Let us return to that period of Octavian's life and work, to that period of Roman history, which can be called preparations for the last stage of the civil war. After the end of hostilities against Sextus Pompey and after the unsuccessful (and fatal for him) attempt by Aemilius Lepidus to oppose Octavian, the triumvirate actually turns into a dual alliance. But the strength of this alliance was also rather illusory; perhaps from this moment Octavian begins preliminary and far-reaching preparations for the decisive battle with his colleague and rival. It carries out a number of activities that are now designed to meet the needs and interests of not only veterans, but also the general population of Italy. He wants to erase all the unfavorable memories for him associated with the initial stage of civil wars after the death of Caesar (about proscriptions, confiscations of land). If now the veterans were rewarded, as usual, with land and money, then this came at the expense of the huge Sicilian booty, and no expropriations were made. Moreover, it was announced that all documents related to the civil war and proscriptions were destroyed, arrears in taxes and farms were accumulated, it was reported that upon the return of Anthony from the Parthian campaign, the old republican system would be completely restored. All these measures were supported by the success of a new foreign policy action - a successful military expedition to Illyria, during which Octavian, together with his commander Agrippa, not only won a number of victories, but this time also showed personal courage.

Thus, if Octavian in the mid-30s managed to somehow strengthen his position and authority, at least among the population of Italy, then this cannot be said about Mark Antony. His Parthian campaign, which began very promisingly and successfully (the siege of the capital of Media), dragged on and, in the end, Antony had to withdraw troops from Media. The retreat took place in difficult conditions, with incessant attacks by the Parthians, and Antony's army suffered heavy losses. According to Plutarch, the campaign lasted 27 days, and the Romans won 18 victories in skirmishes with the Parthians, but these were not complete and decisive successes, because the Romans did not have enough strength to pursue the defeated enemy.

In an official report to the Senate, Antony portrayed the Parthian campaign as a major victory. However, it was not possible to completely hide the truth, and soon rumors spread in Rome, for Antony very little flattering and unfavorable. It did not help that in the next (i.e., in 35) year, Anthony undertook a new and more successful campaign - this time to Armenia. The fact is that after this campaign he made a major political mistake - he celebrated a triumph in Alexandria, which, according to Roman concepts, looked almost like sacrilege. The climax of every triumph was considered to be a sacrifice in the temple of Capitoline Jupiter, therefore, the triumph could only be celebrated in Rome itself.

Moreover, either during the triumph itself, or shortly after it, Antony held a magnificent political demonstration in Alexandria, about which Plutarch tells the following: and lower for sons, he first of all declared Cleopatra queen of Egypt, Cyprus, Africa and Coele-Syria, under the co-rule of Caesarion, who was considered the son of the elder Caesar, who was said to have left Cleopatra pregnant; then he proclaimed the sons whom Cleopatra bore from him kings of kings and appointed Alexander Armenia, Media and Parthia (as soon as this country was conquered), and Ptolemy - Phoenicia, Syria, Cilicia.

It goes without saying that such actions could in no way contribute to the growth of Anthony's authority and popularity in Rome. On the contrary, they were perceived as a challenge, as a hostile act in relation to "everything Roman", and caused a "wave of hatred" against Antony.

Octavian used this favorable moment in time and very subtly. We have already mentioned that the Brundisian agreement was reinforced by a dynastic marriage: Antony married Octavian's sister Octavia. At first, this marriage even looked happy - thanks to the beauty and excellent character of Octavia, but when Antony met Cleopatra again in Antioch in 37, everything was broken. Disregarding the customs and rules, Antony soon, without divorcing Octavia, entered into an official marriage with the Egyptian queen. It was another scandal.

The fate of Octavia, who kept herself impeccable and, remaining in Rome, led the house of Antony and raised his children, aroused general sympathy. When she announced her desire to go to her husband, Octavian did not prevent this, but, as ancient authors noted, not out of a desire to please her sister, but counting on an insulting reception from Antony, which could serve as one of the reasons for war. And so it happened. When Octavia, bringing with her 2 thousand selected soldiers, as well as collecting money and gifts for Antony's commanders and friends, arrived in Athens, she was handed a letter from him, in which, referring to another campaign and employment, he asked her to return back to Rome.

Since that time, open hostility between the former triumvirs begins. They exchange mutual reproaches, accusations, and in 1932, at a meeting of the Senate, a complete break occurs not only between the main actors themselves, but also between their supporters from among the senators. As a result, about 300 senators (including both consuls!) left Rome (with the permission of Octavian) and went to Anthony. By this, in essence, the question of a new war was settled, and both sides are beginning to actively prepare for it.

Antony sends an official divorce to Octavia; in response to this, Octavian, contrary to existing rules, publishes Anthony's testament, which was kept by the vestals. From this will it followed that Antony asked to be buried in Egypt together with Cleopatra, that he secured for her and for her children all those lands and kingdoms that were so solemnly transferred to them.

This testament turned out to be a drop that overflowed the cup. It aroused general indignation in Rome. Cleopatra was declared war. The fact that the war was declared specifically to Cleopatra can be recognized as a new successful action by Octavian, because in this way the upcoming war acquired the character of an external, and by no means civil, which impressed the Romans much more at that moment.

Nevertheless, the war required funds. Octavian had to resort to exceptional measures. All freeborn were to contribute one-fourth of their annual income, and freedmen one-eighth of all property. These measures led almost to uprisings. Plutarch considers Antony’s delay to be the greatest mistake, for he gave Octavian the opportunity to prepare and calm down the unrest, and very wisely remarks that “while the penalties were going on, people were indignant, but, having paid, they calmed down.” Moreover, Octavian managed to ensure that the inhabitants of Italy, Gaul, Spain, Africa, Sicily and Sardinia swore allegiance to him.

Antony, for his part, was no less actively preparing for the coming war. He gathered a considerable army; the fleet, located in Ephesus, consisted of up to 800 ships (including cargo ships), with 200 ships put up by Cleopatra. From her, Antony received 2 thousand talents and food for the entire army. There were two groups or "parties" in Antony's camp: the senators who went over to his side, who wanted either to reconcile him with Octavian, or at least remove Cleopatra for a while, and the "party" of Cleopatra herself, which provoked Antony to the most defiant actions. and a complete break with Rome. The last one won, of course.

While the fleet was being drawn up and the army was being completed, Antony and Cleopatra went to Samos, where they spent all their days in entertainment and pleasure. But let us give the floor again to Plutarch. He writes: “Almost the whole universe was buzzing with groans and sobs, and at this very time, a single island resounded with the sounds of flutes and citharas for many days in a row, the theaters were full of spectators, and the choirs zealously fought for the championship. Every city sent a bull to take part in solemn sacrifices, and the kings tried to surpass each other in the splendor of receptions and gifts, so that the people said with bewilderment: what kind of victorious festivities will they have if they celebrate the preparations for war with such magnificence? . Then Cleopatra and Antony moved to Athens, where endless feasts, celebrations, spectacles stretched again.

When, finally, the opponents moved against each other, under the command of Anthony there were at least 500 warships, 100 thousand infantry and 12 thousand cavalry. On his side were a number of dependent kings and rulers who sent their auxiliary detachments. Octavian had only 250 ships, infantry - 80 thousand, and cavalry also about 10-12 thousand. However, in one respect he had an indisputable advantage - his ships were well equipped and distinguished by greater lightness and maneuverability. Nevertheless, Octavian offered Antony to solve the matter by a land battle, promising to ensure that his army landed in Italy. Antony refused and instead offered Octavian to fight him in a duel.

The decisive battle took place on September 2, 31 at sea, near Cape Promotions in Epirus. The battle was quite stubborn, its outcome was still absolutely unclear, when suddenly, in full view, 60 ships of Cleopatra raised sails to sail and took to flight, making their way through the thick of the fighting. Antony, as soon as he noticed that Cleopatra's ship was leaving, forgot about everything in the world and, leaving to the mercy of fate the people who fought and died for him, switched from the flagship to the fast penther and rushed in pursuit of Cleopatra.

The naval battle, however, continued until late in the evening. Only very few saw the flight of Antony with their own eyes, and those who knew about it did not want to believe that the illustrious commander could so shamefully abandon his fleet, and besides 19 completely intact legions and 12 thousand cavalry. And although the fleet was nevertheless defeated, the ground army did not want to leave the camps for another whole week, rejecting all the profitable offers that Octavian made. And only when the military leaders themselves began to secretly flee from the camp at night, the soldiers had no choice but to go over to the side of the winner.

The Battle of Actia decided in principle the outcome of the civil war. But the war as such was by no means over yet. Before moving on to the final goal - the capture of Egypt, Octavian, as always extremely thorough and cautious, takes a number of measures that secure his position in the East. He goes first to Athens, where he takes initiation into the Eleusinian mysteries. Then he sails to Samos, and from there to the cities of Asia Minor. Here, in search of popularity, he pursues the traditional policy of adding up debts and abolishing taxes, and also bestows the rights of Roman citizenship to the natives of the eastern cities who served in his army. At the end of 31, Octavian was forced to return to Italy - he was informed of a major rebellion of veterans. The soldiers, as always, demanded money and land. Based on future Egyptian booty, Octavian satisfied all their demands, although for this he had to spend almost all of his own funds and even borrow significant amounts from friends. After that, he was able to resume his eastern campaign.

As for Antony, he used the respite given to him by Octavian in a rather strange way. After several months of depression, which he spent alone, he returned to Alexandria, to Cleopatra. And although the most disappointing information came to him, saying that the kings and dynasts subject to him, starting with the Jewish king Herod, one after another change and go over to the side of Octavian, so that nothing remains for him but Egypt, he, according to Plutarch, as if rejoicing, he renounced all hope and began to amuse the city with endless feasts, drinking parties and cash distributions. He wrote down Caesarion in ephebes, that is, he declared him an adult in the Greek way, and he dressed his son from Fulvia in a man's toga. On this occasion, a multi-day festival was arranged for all the inhabitants of Alexandria. Then Antony and Cleopatra founded the "Union of Suicide Bombers", where friends who decided to die with them, but so far took turns asking feasts, one more luxurious than the other, signed up.

However, they nevertheless sent ambassadors to Octavian. Cleopatra asked to transfer power over Egypt to her children, and Antony - to allow him to spend the rest of his days as a private person either in Egypt or in Athens. Octavian categorically rejected Antony's request, but Cleopatra replied that she would be granted full indulgence if she extradited or killed Antony. Octavian at that time tried in every possible way to emphasize his gracious attitude towards Cleopatra also because she transferred innumerable riches from the royal treasury to her mausoleum and threatened to burn it all and commit suicide.

When Octavian's troops approached Alexandria, in one of the first skirmishes, Antony put the enemy cavalry to flight. Excited by the battle, he returned to the palace and, without taking off his armor, kissed Cleopatra and introduced her to one of the most distinguished warriors. The queen rewarded him with a golden shell and a helmet. Having received this award, the distinguished soldier defected to Octavian the same night.

Soon the same betrayal was repeated, but on a much larger scale.

Antony again sent Octavian a challenge to a duel. He answered that to him, Anthony, many roads to death were open. Then Antony decided to give battle at the same time on land and at sea. However, it was in this battle that his fleet went over to the side of Octavian, the cavalry did the same, and the infantry was defeated.

It was the end. Antony, falling into despair, began to accuse Cleopatra of betrayal. In fear of his anger, she took refuge in the tomb, and she ordered him to report her death. Antony believed this and stabbed himself with a sword. Then he was taken to the tomb of the queen, and he died in the arms of Cleopatra, who had been forgiven by him. Thus ended the fate of this brilliant adventurer. When Octavian received news of his death, he "went into the depths of the tent and wept, grieving for the man who was his relative, co-ruler and comrade in many deeds and battles."

The fate of Cleopatra was ultimately no less tragic. When she became Octavian's prisoner and convinced that at best he would spare her life, but intended to lead her in triumph, she committed suicide. According to legend, she died from a snakebite delivered to her - despite protection - in a basket of berries.

Octavian executed Caesarion and Antony's eldest son, Antillus. The rest of Cleopatra's children by Antony were led in triumph and then brought up by Octavia along with her children by Antony. Egypt was converted into a Roman province, and it became the first province that was no longer ruled by the senate, but by the emperor himself through his representatives. Octavian, upon returning to Italy, celebrated a magnificent triumph that lasted three days: the first day - for Illyria, the second - for the victory over Cleopatra at Action, the third - for the capture of Alexandria. Thus, it was again emphasized that victories were won against external enemies, and by no means over Roman citizens.

Nevertheless, these were, of course, civil wars. Octavian emerged victorious from them. He managed, as Tacitus says, to win over the army with gifts, the people with the distribution of bread, and everyone in general with the sweetness of the world. This world was a desirable dream for almost all segments of the population of a huge power. The one who could now ensure a lasting, lasting peace with a firm and skillful leadership, was expected by general worship and almost divine honors. And so it happened. Therefore, when at the meeting of the Senate on January 13, 27 BC. e. Octavian announced the resignation of emergency powers, the senators unanimously and unanimously - although, as Dio Cassius says, some sincerely, while others only out of fear - convinced him to once again assume supreme power. And three days later, the grateful Senate presented him with the honorary title of Augustus. From that time on, Octavian began to be officially called "emperor Caesar Augustus, son of the divine." In addition, from that time on, he was always listed first in the lists of senators, that is, he became the princeps of the senate, or, as Augustus himself later emphasized, "first among equals." Usually 27 BC e. is considered the date that opens a new era - the era of the principate, or, as they say much more often, the era of the Roman Empire.

The nature of the political system that has been established in Rome since the reign of Augustus has caused and still causes no less controversial judgments than the personality of the "first Roman emperor" himself. These disagreements began in ancient historiography.

First of all, a document compiled by Augustus himself and published by his successor Tiberius, which is called the "Acts of the divine Augustus." In this document, Octavian Augustus, with all the persuasiveness available to him, tries to prove that he "returned freedom to the state" (republic), that he "transferred the state (republic) from his power to the disposal of the senate and the people."

So, the "restored republic" (res publica restituta) - this was the official slogan that Augustus himself spoke, therefore, it was supposed to consider all his activities in this way, allegedly such was its main and ultimate goal. Indeed, this is how the representatives of the apologetic trend in Roman historiography portrayed it. For example, Velleius Paterculus, closest in time to the era of Augustus, wrote: “... the original and ancient form of the state was returned”, that is, in other words, the republic was restored.

Tacitus, who, as already mentioned, in characterizing Augustus, did not express his own point of view, but cited the existing opinions about him equally both for and against, in this case, i.e., evaluating the political system established by Augustus, also did not avoids obviously contradictory judgments. In one place - this has already been said - he believes that Augustus gave the state a structure without dictatorship and without royal power, but in another place he emphasizes that the peace established by Augustus went to the Romans at the cost of losing freedom, or claims that the tribunician power (tribunicia potestas) Augustus accepted not only not to take the name of the king, but at the same time to surpass everyone with his power. Generally speaking, Tacitus believes that Augustus seized power in the state, usurped it, and the political system he established later degenerated into open and obvious tyranny.

Dio Cassius, who treats Augustus very positively, nevertheless has no doubt that Augustus established autocracy. However, this monocracy is not absolute and intolerable - the Senate and its members enjoy great influence and honor. The supreme power itself, which Augustus possesses, is by no means the result of usurpation, but was handed over to him only for a certain period and precisely by the senate.

Thus, in ancient historiography, there were, as it were, two options for defining the political system established by Augustus. The official variant qualified this system as a "restored republic" (or "state"), the unofficial variant (presented, as a rule, by later authors) defined the system as an autocracy.

It should be noted that the new historiography did not bring much diversity to this issue. Perhaps the most original characterization of the principate (and the power of Augustus) was expressed in his time by Mommsen. He was not interested in the question of the genesis of the principate, which was determined by his fundamental principles. In those works in which Mommsen defines the principate, he deals not with history, but with the system of Roman law. Therefore, it departs from legal precedents.

Approaching the definition of imperial power from these positions, Mommsen speaks of the proconsular empire (imperium proconsulare) and tribunic power (tribunicia potestas) as the two fundamental foundations of this power. The same political system that has been established in Rome since 27, i.e., the formal division of power between the emperor and the senate, which continued de iure to remain further, is defined by Mommsen not as a republic and not as a monarchy, but as a kind of peculiar form of dual power. what he calls diarchy.

Another scholar of the principate, Hardthausen, took a different view. He substantiated one of the variants of the ancient tradition, believing that the "restoration of the republic" by Augustus is an obvious fiction and the power of Augustus was purely monarchical in nature. A specific feature of this power was the unusual combination in the hands of one person of the usual Roman magistracies. This was precisely the magisterial basis of the Augustan monarchy.

A special, as already mentioned, point of view on the principate and on the power of Augustus was developed by Ed. Meyer. In his opinion, the principate as a special political form was formed under Pompey. Caesar's adopted son was by no means the heir and continuer of his father's political doctrine, for Julius Caesar sought to establish a Hellenistic type of monarchy. In terms of state creativity, Augustus should be considered the successor of the work of Pompey. A principate is such a political system when all power belongs to the senate, the “guardian” of which is the princeps. Thus, it is by no means a monarchy or "diarchy", but a truly restored republic.

All these points of view, especially the last two, have varied in modern historiography an infinite number of times. We cannot dwell on these "variants", because for this we would have to touch on many works. It is only worth noting, perhaps, that M. I. Rostovtsev in his fundamental work “The Socio-Economic History of the Roman Empire” essentially renounces the definition of the principate; R. Syme, as a matter of fact, does the same (in the repeatedly mentioned work "The Roman Revolution"). By the way, Syme absolutely rightly objects to the attempts to legally substantiate the power of Augustus.

Finally, the Soviet researcher of the principate, N. A. Mashkin, believes that even if the republic was officially “restored,” there is still a lot to confirm the monarchical essence of Augustus’ power. This, in his opinion, is evidenced by the concept of auctoritas, as well as the titles of princeps and emperor. Thus, in contrast to Mommsen, one can speak of non-magisterial, but purely Roman sources of sole power. As for the magistrate's powers, although they are of great importance, this is by no means a substance, but only a formalization of power. In this sense, the power of Augustus consisted of ordinary Roman powers, with the only exception that he combined in his hands magistracies and functions that were incompatible during the years of the classical republic (ordinary and extraordinary magistracies, priestly functions, etc.).

In conclusion, a few words about our understanding of the nature of the political system established by Augustus. In this case, we do not pretend to study the problem of the principate, or even to a precise definition of its essence, but, mindful of the well-known rule that all phenomena and events are better known in comparison, we will only try to compare, give a comparative description of the "regimes" of Caesar and Augustus . Moreover, we are not going to make this comparison in terms of: monarchy - diarchy - republic or Hellenistic monarchy - principate, or, finally, in terms of clarifying the state-legal foundations of the principate, since all these aspects of the problem should be considered basically the creation and construction of new historiography. Disregarding these, strictly speaking, modernizing constructions, we will only try to compare some characteristic features of the "regimes" of Caesar and Augustus. Moreover, we use this term conditionally, with the proviso that we consider these “regimes” not so much the product of the activity or creation of named historical figures, but rather the product of a certain situation and conditions of the socio-political struggle.

Given this reservation, we consider it quite possible to assert - in contrast to the above point of view, Ed. Meyer - the fact that Augustus, in principle, was a consistent student and successor of Caesar. However, apart from the difference in temperaments, it is necessary first of all to emphasize the difference in methods, about which, not without wit, it was noted that Augustus, as it were, slowed down the pace taken by Caesar in his time, and to such an extent that it seemed that he not so much continues the political line of his adoptive father, but opposes himself to it, although in reality this is not at all the case.

Arguing in this regard about Augustus, obviously, one should keep in mind at least two circumstances: a) Augustus by no means indiscriminately continued everything that was done or only outlined by Caesar, but, so to speak, “creatively” selected or discarded individual elements this inheritance; b) something that Augustus had already taken away and that in Caesar, as a rule, was brought to life by “current needs”, and therefore looked like only a hint or an isolated action, Augustus developed into a “system”. At the basis of these methods and features lay a deeper difference - the difference between the actions of the leader of "democracy" and the statesman. That is why the "regime" of Caesar was nothing more than the sum of individual events - albeit sometimes very talented, timely, and even of great national importance - but by no means a system and not even a regime, while the "regime" of Augustus is already clearly a government system.

Obviously, one should get acquainted with this "system", at least in its most general, but at the same time, its most characteristic features. First of all, the "regime" of Augustus differed from Caesar's if only in that - and this point should by no means be considered secondary, lightweight, not deserving serious attention - that the form of government established under Augustus received an officially recognized name. It was, as has already been pointed out, a "restored republic" (res publica restituta), and such an assertion was supported by all the power of government propaganda. By the way, it was under Augustus that political propaganda began to be given extremely importance and for the first time it acquired the features of a state enterprise.

Consequently, any open disagreement with the official name of the existing regime could be regarded as harmful dissent, as a kind of opposition, and therefore, depending on the will of the princeps, could be more or less resolutely suppressed. In any case, a standard certified by the state was given. The fatal mistake of Caesar as a political figure was the unfortunate circumstance that his "regime" had no officially expressed name and, consequently, the possibility of its definition was provided, as it were, to the citizens themselves. The latter, for some reason, quite unanimously defined it only as regnum, tyranny, etc.

Did the official name given by Augustus to his regime correspond to its internal content? Of course not! This was perfectly understood by Augustus himself, it was understood or, in any case, could be understood by his contemporaries and subjects, but this was no longer of decisive importance. It hardly really matters how seriously Augustus' contemporaries believed that he was a god; the only important thing is that officially it was considered as such, and quite real altars and temples were erected in his honor. The same is the case with the slogan res publica restituta, which was no longer only a slogan, but also an officially recognized definition of a real state system.

But from what has been said, it follows that the "principle of Augustus" is perhaps the first example in history of a regime based on political hypocrisy, and even elevated to a principle. This is a state system (with the passage of time quite clearly formed and expressed), which, quite consciously and cynically, was presented by official propaganda not at all for what it really was. However, with such an understanding of the "regime" of Augustus, i.e., the essence of the "principate", the secondary, auxiliary significance of those of his attributes, which were often taken at face value by many researchers, becomes more than obvious. Such attributes certainly include the notorious auctoritas of Augustus, which (since the discovery of the inscription, usually called the Monumentum Antiochenum) has become the focus of attention of all researchers of the principate and which is either recognized or, on the contrary, is not recognized as the state legal basis of this political regime. The same can be said about all other attempts to understand the essence of the principate, proceeding from the formal legal criteria and concepts.

What, from our point of view, are not the formal-legal, not the state-legal, but the socio-political foundations of the “principle” of Augustus? There are several of these foundations, and in the first place among them we consider it necessary to put nothing but a new bureaucratic apparatus of the empire. We put him in first place, although we are fully aware of the fact that he could not become the main support of the imperial regime already under Augustus. However, if we consider the role of the government apparatus in the future, then there is no doubt that in the future it turns into a similar support for the new regime, and so much so that it even becomes possible to speak of the “dictatorship of the apparatus” (in relation to the late empire).

The enormous increase in the role of the apparatus is due to the fact that it was called upon to supplant the elected (and most democratic!) bodies of the polis-republican structure of Rome. We can trace this process of repression from the time of Caesar. For example, as mentioned above, Caesar, leaving for the last time for the war in Spain, appointed praefecti urbis to govern Rome during his absence, replacing them with elected magistrates. The appointment of city prefects was repeatedly practiced by Augustus (and his successors). In addition, procurators appointed by Augustus, legates, prefects of the praetorium and imperial provinces, as well as friends (amici) and companions (comites) of the emperor, become the links of the government apparatus.

From what social environment was the bureaucratic apparatus recruited under Augustus? In accordance with the traditions that existed back in republican times, dating back to the creation of an apparatus under the governors of the provinces, Augustus replenished the government apparatus to a large extent with people who were personally dependent on him in one form or another: clients, freedmen, slaves.

The second, and no less important basis of the new regime, we consider, of course, the army. The Roman army in the period of civil wars after the death of Caesar was no less politically important and used as a political organization no less than under Caesar. But when a lasting peace is established and the position of Augustus as an autocrat is established, the tasks that confronted him in relation to the army, of course, change significantly. The "dictatorship of the legions" is now out of the question. The army, as a political force and political pillar of the new regime, undoubtedly remains, but it must be introduced within certain limits, it must be "curbed", that is, it must cease to exist as an independent political factor. Augustus fulfilled this task by carrying out, as some researchers believe, the following reform: replacing the "extraordinary" armies of the republican era with a standing army in peacetime, but on a wartime scale. In addition, Augustus made an important change in the position of the officer corps, linking officer and civilian careers. In this way, he managed to avoid two dangers: an army saturated with professional officers, and, conversely, an army in which only soldiers, but not their command staff, are professionals. The compromise found by Augustus turned out to be extremely successful, it became the cornerstone of his entire military reform. According to other researchers, Augustus managed to “split the united front of centurions and soldiers” by the fact that he did not hesitate, contrary to custom, to promise, when it was beneficial to him, Senate posts to centurions. He did this occasionally, but he began to systematically allow persons belonging to the equestrian class to occupy senior officer positions without prior service in the army. Thus, the "centurion corps" began to gradually differentiate.

We consider the new strata of the ruling class, more precisely, the ruling class in its transformed form, to be the next most important pillar of the Augustan regime. What is to be understood by this transformation has already been explained above. Like Caesar - perhaps even more consistently - Augustus sought to send representatives of this class into the "channel" of the senate. The Senate, as is known, played a prominent role in the reign of Augustus, but the relationship between the senate and the princeps was rather complicated. Augustus, of course, extremely reckoned with the Senate, but at the same time sought to keep its activities under constant control, not to mention the fact that he took a direct part in shaping the composition of the Senate.

From the book From Pharaoh Cheops to Emperor Nero. The ancient world in questions and answers author Vyazemsky Yuri PavlovichOctavian Augustus (63 BC - 14 AD) Question 6.54 According to legend, Octavian Augustus' mother, Atia, never went to public baths. Why, may I ask? at the age of three, Octavian (then his name was Octavius) repeated the Italian feat

From the book From Pharaoh Cheops to Emperor Nero. The ancient world in questions and answers author Vyazemsky Yuri PavlovichOctavian Augustus (63 BC - 14 AD) Answer 6.54 According to legend, Atia gave birth to her great son not from her husband, Gaius Octavius, but from the god Apollo, who appeared to her in the form of a serpent. After such a visit, a stain in the form of a snake formed on the woman’s body, from which she did not

From the book Extracts on the life and customs of the Roman emperors author Aurelius Victor SextusChapter I Octavian Augustus In the year 722 from the founding of the city and the 480th year from the expulsion of the kings, the custom was again established in Rome in the future to obey one, but not the king, but the emperor, or called by a more sacred name, Augustus. (2) So

From the Acts of the Divine Augustus author August OctavianThe acts of the divine Augustus Gaius Julius Caesar Octavian Augustus The acts of the divine Augustus, with which he conquered the earthly circle of power of the Roman people, and the donations that he made to the state and the Roman people, carved on two bronze pillars, which

From the book On the Caesars author Aurelius Victor SextusChapter I Octavian Augustus About the year 722 from the founding of the city, also in Rome, the custom was established in the future to obey one [ruler] (2). Indeed, the son of Octavius Octavian, adopted by the great Caesar, his great-nephew soon after received from

From the book Ancient Rome author Mironov Vladimir Borisovich From the book of 100 great monarchs author Ryzhov Konstantin VladislavovichOCTAVIAN AUGUST Octavian, or, as he was called in childhood and youth, Octavius was the great-nephew of the famous Roman commander Gaius Julius Caesar (his maternal grandmother, Julia, was the emperor's sister). Caesar, who had no male offspring, declared

From the book History of Ancient Rome in biographies author Stol Heinrich Wilhelm35. Gaius Julius Caesar Octavian Augustus Octavian, born September 23, 63 BC, was originally called, like his father, Gaius Octavius, but then, becoming the adopted son of the dictator Caesar, took the name of G. Julius Caesar Octavian. His mother, Attia, was the daughter of a younger sister.

From the book World History in Gossip author Baganova MariaHeir - Octavian August Gaius Octavius was Caesar's great-nephew. The boy was raised by his mother - loving, but extremely domineering. Historian Nikolai Damascus: “Although by law he was already ranked among adult men, his mother still did not allow

From the book World Military History in instructive and entertaining examples author Kovalevsky Nikolay FedorovichAugust Octavian. Antony and Cleopatra Octavian quarrels with Mark Antony The wise Caesar, unexpectedly for many, bequeathed his inheritance to his great-nephew Octavian, a very worthy young man. The latter established an alliance with Caesar's associate Mark Antony and

From the book Imperial Rome in Persons author Fedorova Elena V From the book World History in Persons author Fortunatov Vladimir Valentinovich3.1.2. The first Roman Emperor Octavian Augustus Octavian Augustus was the grandson of Julius Caesar's sister. Shortly before his death, Caesar adopted him. After the adoption, Octavian's full name was Gaius Julius Caesar Octavian. After the death of Caesar, Octavian made the second

author Muravyov MaximOctavian August is Rurik Rostislavich Octavian August (63 BC - 14), Rurik Rostislavich (died in 1211, 1212 or 1215), i.e. the year of death is about the same, plus 1200 years. And the year of birth of Rurik is unknown, but for the first time it is mentioned in 1157, he fights at Turov, that is, you can

From the book Crazy Chronology author Muravyov MaximAgrippa is Octavian August If Mstislav is combined with both Agrippa and Vsevolod=August, then Agrippa simply must be Augustus. What do we see? In Russia, one prince is described several times under different names. Why couldn’t the “Italian” history

From the book General History [Civilization. Modern concepts. Facts, events] author Dmitrieva Olga VladimirovnaOctavian Augustus and the Establishment of the Principate The hero of the Battle of Actium understood perfectly well that the transition to an open form of a monarchical regime would be dangerous for the time being. The tragic example of the conspiracy against Caesar was very revealing. In wide sections of Roman society

From the book World History in Sayings and Quotes author Dushenko Konstantin VasilievichSend your good work in the knowledge base is simple. Use the form below

Students, graduate students, young scientists who use the knowledge base in their studies and work will be very grateful to you.

Posted on http://www.allbest.ru/

Introduction

1. The main reasons for the transition from a republican form of state to an empire. Rise of an empire

2. Roman Empire: main periods of development

2.1 Principate and its essence

2.2 Roman Dominate

3. The collapse of the Western Roman Empire

Conclusion

Bibliography

empire roman council of state

Introduction

The Roman state occupies a special place in the history of the legal development of mankind and modern jurisprudence, as well as, in fact, Roman law, since it was this system, which once became uniform for the ancient world, that formed the basis of the law of many modern states.

The history of the Roman Empire is usually divided into three periods. The period of formation, heyday and fall. Most historians consider the 3rd century A.D. to be a turning point. e. , which occupied a special place in this history, separating the period of the Early Empire (Principate) from the period of the Late Empire (Dominat). It is usually noted that the Roman state in this century was in a state of crisis, and the period itself is called the period of crisis of the III century. Although there is a very extensive historiography for this period of Roman history, a number of aspects of the problem of the crisis cannot be considered definitively resolved and continue to be the subject of controversy. Therefore, the relevance of the study of the formation, development and fall of the Great Roman Empire is not lost over time, but rather acquires a unique scientific interest.

The purpose of this work is to study the formation, development and fall of the Roman Empire (I century BC - V AD).

To achieve the goal, the following tasks were set:

Determine the reasons for the transition from a republican form of state to an empire;

To characterize the most important periods in the development of the Roman Empire: principate and dominate;

Analyze the causes of the fall of the Roman Empire.

The course work consists of an introduction, three chapters, a conclusion and a list of references.

1. Mainthe reasonstransitionfromRepublicanformsstatestoempire.Formationempire

In the II-I centuries. BC. the development of a slave-owning society in Rome leads to an aggravation of all its class and social contradictions. Shifts in the economy, the expansion and change in the forms of exploitation of slave labor, its intensification were accompanied by intensification of conflicts between groups of the ruling upper classes of slave owners, as well as between them and the majority of the free, the poor and the poor. The successful policy of conquest, which turned the Mediterranean into an inland sea of the Roman state, subjugated to it almost all of Western Europe up to the Rhine, confronted Rome with new complex military and political problems of suppressing the conquered peoples and ensuring their control.

Under these conditions, it becomes more and more obvious that the old political system is already powerless to cope with the contradictions that have arisen and aggravated. Rome enters a period of crisis, which affected, first of all, the existing political institutions, the outdated polis form of government, the aristocratic political regime of the nobility, disguised by the republican form of government, which created the appearance of the power of the Roman people. There was an objective need for their restructuring, adaptation to new historical conditions.

During the conquest of Italy in the V-IV centuries. BC. Rome sought, above all, to confiscate land, as population growth required the expansion of land holdings. This trend was not stopped by the intensive urbanization that developed by the 2nd century BC. BC. Wars II - I centuries. BC. somewhat shifted the emphasis - they were accompanied by the massive enslavement of the conquered population, which led to a sharp increase in the number of slaves in Rome. Slavery acquires a "classical", antique character. A significant mass of slaves are exploited in state and large private landowning latifundia with extremely difficult working and subsistence conditions and a brutal terrorist regime. The natural protest of the slaves results in a series of ever wider and more powerful uprisings. Slave uprisings in Sicily in the 2nd century BC had a particularly large scale. BC. and an uprising led by Spartacus 74-70. BC, which threatened the very existence of the Roman state.

In parallel with the slave uprisings and after them, civil and allied wars flare up, caused by the struggle for power between the factions of the ruling class, the contradictions between it and the small producers and the increased (up to 300,000) mass of lumpen proletarians who received insignificant material assistance from the state. The growth in the number of lumpen becomes convincing evidence of the general degradation of the free.

The economic and political dominance of the nobles caused in the II century. BC. a broad protest movement of the poor, led by the brothers Tiberius and Gaius Gracchi. The Gracchi sought to limit the large land ownership of the nobility and thereby create a land fund for allocating land to small landowners, as well as weaken the power of the stronghold of the nobility - the Senate and restore the lost power of the people's assembly and the people's tribune.

Having received the position of tribune, Tiberius Gracchus, relying on the popular movement, managed, despite the resistance of the senate, to hold in 133 BC. through the People's Assembly Agrarian Law. The law limited the maximum amount of land received from the state. Due to the withdrawn surplus, a land fund was created, distributed among landless or land-poor citizens. The plots they received became inalienable, which was supposed to prevent the dispossession of the peasantry. Despite the fact that Tiberius Gracchus was killed in the same year, his land reform began to be carried out, and several tens of thousands of citizens received land.

The reforming activity of Tiberius was continued by his brother Gaius Gracchus, who was elected tribune. He passed laws that weakened the political influence of the nobility - the introduction of secret ballot in the national assembly, the right of the people's tribune to be elected for the next term. Carrying out the agrarian reform of his brother, Guy, however, in 123-122. BC. passed laws on the creation of colonies of Roman citizens in the provinces with allotment of land to them and on the sale of grain from state warehouses to citizens at very low prices. The last law limited the important right of the Senate - to dispose of public expenditures, since the financing of the sale of grain passed to the people's assembly, the role of which increased significantly.

Guy also carried out military reform. The number of military campaigns obligatory for Roman citizens was limited, military duty was canceled for citizens who had reached the age of 46, soldiers began to receive salaries and weapons from the state and could appeal against the death penalty to the people's assembly.

Along with these activities, in the interests of the lower strata of Roman citizens, Gaius Gracchus also carried out activities in the interests of the horsemen. In their favor, the order of paying off taxes from the provinces was changed.

Finally, since Gaius Gracchus was a tribune, the role of this magistracy increased, pushing even the consuls into the background. However, having satisfied the interests of the majority of Roman citizens, Gaius lost their support in an attempt to extend the rights of Roman citizenship to the free inhabitants of Italy. The Senate aristocracy managed to fail this bill, unpopular among the Roman citizens, Guy's popularity fell, he was forced to resign as a tribune and in 122 BC. was killed.

The extreme aggravation of the political situation in Rome, caused by slave uprisings, the dissatisfaction of small landowners whose farms fell into decay, could not compete with large latifundia as a result of the participation of the owners in endless military campaigns, allied and civil wars, demanded the strengthening of central state power. The inability of the old political institutions to cope with the complicated situation is becoming more and more obvious. Attempts are being made to adapt them to new historical conditions. The most important of these was undertaken during the dictatorship of Sulla (82-79 BC). Relying on the legions loyal to him, Sulla forced the senate to appoint him dictator for an indefinite period. He ordered the compilation of proscriptions - lists of his opponents who were subject to death, and their property - to confiscation. By increasing the number of senators and abolishing the position of censor, he filled the Senate with his supporters and expanded its competence. The power of the tribune was limited - his proposals must first be discussed by the senate - as well as the competence of the people's assembly - judicial powers and control over finances, returned to the senate, were removed from it.

The establishment of a lifelong dictatorship revealed the desire of the nobles and the top horsemen to get out of the crisis situation by establishing a strong one-man power. It also showed that attempts to adapt the old state form to new historical conditions are doomed to failure (Sulla's reforms were canceled by Pompey and Crassus). After the Allied War 91-88. BC. The inhabitants of Italy received the rights of Roman citizens. If before it about 400,000 people enjoyed these rights, now their number has increased to two million. The inclusion of allies in the Roman tribunes led to the fact that the comitia ceased to be organs of the Roman people. Their legislative activity is suspended, the right to elect officials is lost. Successful wars of conquest turned Rome from a small state-city into the capital of a huge state, for the management of which the old state form of the policy was completely unsuitable.

The establishment of a lifelong dictatorship and civil wars have shown that a professional mercenary army is turning into an important political factor. Interested in the successes of the commander, she becomes in his hands an instrument for achieving ambitious political goals, and contributes to the establishment of a dictatorship.

The need to get out of an acute political crisis, the inability of the old state form to new historical conditions and the transition to a mercenary army were the main reasons for the fall of the polis-republican system in Rome and the establishment of a military dictatorial regime.

A short time after Sulla's dictatorship, the first triumvirate (Pompeii, Krase, Caesar) seizes power. After him, the dictatorship of Caesar is established, who received in 45 BC. the title of emperor (previously given sometimes as a reward to the commander). Then a second triumvirate is formed (Anthony, Lepidus, Octavian) with unlimited powers "for the establishment of the state." After the collapse of the triumvirate and the victory over Antony, Octavian received the title of emperor and life-long rights of the people's tribune, and in 27 BC. -- the authority to govern the state and the honorary title of Augustus, previously used as an appeal to the gods. This date is considered the beginning of a new period in the history of the Roman state - the period of the empire.

Thus, from the 30s BC. a new historical era begins in the history of the Roman state and the ancient world in general - the era of the Roman Empire, which replaced the Roman Republic. The fall of the republican form of government and the birth of the monarchical system in Rome was not a minor episode in the socio-political struggle.

The fall of the Roman Republic and the establishment of the Roman Empire was an event of great historical significance, a radical socio-political upheaval, a revolution caused by the restructuring of traditional socio-economic and political institutions. The basis of perestroika was the transformation of the polis-communal organization as a comprehensive system into a structure of a different type.

The history of imperial Rome is usually divided into two periods: the first period of the principate, the second - the period of dominance. The border between them is the III century. AD

The period of the empire is usually divided into two stages:

1. principle (1-3 centuries BC);

2.dominate (3rd-5th century BC).

2. Romanempire:mainperiodsdevelopment

2.1 Principateandhisessence

The social structure of Rome during the principate. After the victory of the great-nephew and successor of Julius Caesar - Octavian - over his political opponents (during Action 31 BC), the Senate handed Octavian supreme power over Rome and the provinces (and presented him with the honorary title of Augustus). At the same time, a state system was established in Rome and the provinces - principate. For Augustus, "princeps" meant "the first citizen of the Roman state", and in accordance with the unwritten Roman Constitution, the office of emperor. In the person of the princeps, power was concentrated, which was usually divided into the following elements.

1. As a military commander, the emperor has the right to complete and uncontrolled control of those provinces in which troops are usually stationed.

2.imperium proconsulare, that is, the right of a general proconsul to govern senatorial provinces.

3. tribunicia potestas, which gives the emperor the quality of sacronsanctus and the right of intercessio in relation to all republican magistrates.