The fertile climate, the picturesque and generous nature of Taurida create almost ideal conditions for human existence. People have long inhabited these lands, so the eventful history of Crimea, which goes back centuries, is extremely interesting. To whom and when did the peninsula belong? Let's find out!

History of Crimea since ancient times

Numerous historical artifacts found by archaeologists here suggest that the ancestors modern man fertile lands began to settle almost 100 thousand years ago. This is evidenced by the remains of Paleolithic and Mesolithic cultures found in the site and Murzak-Koba.

At the beginning of the XII century BC. e. tribes of Indo-European nomadic Cimmerians appeared on the peninsula, whom ancient historians considered the first people who tried to create in the beginnings of some kind of statehood.

At the dawn of the Bronze Age, they were forced out of the steppe regions by warlike Scythians, moving closer to sea coast. The foothill areas and the southern coast were then inhabited by Taurians, according to some sources, who came from the Caucasus, and in the north-west of the unique region Slavic tribes who migrated from modern Transnistria.

Ancient heyday in history

As the history of the Crimea testifies, at the end of the 7th century. BC e. it began to be actively mastered by the Hellenes. Natives of the Greek cities created colonies, which eventually began to flourish. fertile land gave excellent harvests of barley and wheat, and the presence of convenient harbors contributed to the development of maritime trade. Crafts actively developed, shipping improved.

Port policies grew and grew richer, uniting over time into an alliance that became the basis for creating a powerful Bosporan kingdom with its capital in, or present-day Kerch. The heyday of an economically developed state with a strong army and an excellent navy dates back to the 3rd-2nd centuries. BC e. Then an important alliance was concluded with Athens, half of whose needs in bread were provided by the Bosporans, their kingdom includes lands Black Sea coast behind Kerch Strait, Theodosius, Chersonese are blooming,. But the period of prosperity did not last long. The unreasonable policy of a number of kings led to the depletion of the treasury, the reduction of military personnel.

The nomads took advantage of the situation and began to ravage the country. at first he was forced to enter the Pontic kingdom, then he became a protectorate of Rome, and then of Byzantium. The subsequent invasions of the barbarians, among which it is worth highlighting the Sarmatians and Goths, further weakened him. Of the once magnificent settlements, only the Roman fortresses in Sudak and Gurzuf remained undestroyed.

Who owned the peninsula in the Middle Ages?

From the history of the Crimea it can be seen that from the 4th to the 12th centuries. Bulgarians and Turks, Hungarians, Pechenegs and Khazars marked their presence here. The Russian prince Vladimir, having taken Chersonese by storm, was baptized here in 988. The formidable ruler of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Vytautas, invaded Tauris in 1397, completing the campaign in. Part of the land is part of the state of Theodoro, founded by the Goths. To middle of XIII For centuries, the steppe regions have been controlled by the Golden Horde. In the next century, some territories are redeemed by the Genoese, and the rest are submitted to the troops of Khan Mamai.

The collapse of the Golden Horde marked the creation here in 1441 of the Crimean Khanate,  self-existing for 36 years. In 1475, the Ottomans invaded here, to whom the khan swore allegiance. They expelled the Genoese from the colonies, took by storm the capital of the state of Theodoro - the city, having exterminated almost all the Goths. The khanate with its administrative center in was called Kafa eyalet in the Ottoman Empire. Then finally formed ethnic composition population. Tatars are moving from a nomadic lifestyle to a settled one. Not only cattle breeding began to develop, but also agriculture, horticulture, small tobacco plantations appeared.

self-existing for 36 years. In 1475, the Ottomans invaded here, to whom the khan swore allegiance. They expelled the Genoese from the colonies, took by storm the capital of the state of Theodoro - the city, having exterminated almost all the Goths. The khanate with its administrative center in was called Kafa eyalet in the Ottoman Empire. Then finally formed ethnic composition population. Tatars are moving from a nomadic lifestyle to a settled one. Not only cattle breeding began to develop, but also agriculture, horticulture, small tobacco plantations appeared.

The Ottomans, at the height of their power, complete their expansion. They move from direct conquest to a policy of covert expansion, also described in history. The Khanate becomes an outpost for raids on the border territories of Russia and the Commonwealth. The looted jewels regularly replenish the treasury, and the captured Slavs are sold into slavery. From the 14th to the 17th centuries Russian tsars undertake several trips to the Crimea through the Wild Field. However, none of them leads to the pacification of a restless neighbor.

When did the Russian Empire come to Crimean power?

An important stage in the history of Crimea -. To early XVIII in. it becomes one of its main strategic goals. Possession of it will allow not only to secure land border from the south and make it inland. The peninsula is destined to become the cradle of the Black Sea Fleet, which will provide access to the Mediterranean trade routes.

However, significant progress in achieving this goal was achieved only in the last third of the century - during the reign of Catherine the Great. The army under the leadership of General-in-Chief Dolgorukov captured Taurida in 1771. The Crimean Khanate was declared independent, and Khan Girey, who was a protege of Russian crown. Russian-Turkish war 1768-1774 undermined the power of Turkey. Combining military force with cunning diplomacy, Catherine II ensured that in 1783 the Crimean nobility swore allegiance to her.

After that, the infrastructure and economy of the region began to develop at an impressive pace. Here settle retired Russian soldiers.  Greeks, Germans and Bulgarians come here en masse. In 1784, a military fortress was laid, which was destined to play a prominent role in the history of the Crimea and Russia as a whole. Roads are being built everywhere. Active cultivation of grapes contributes to the development of winemaking. The southern coast is becoming more and more popular among the nobility. turns into a resort town. For a hundred years, the population of the Crimean peninsula has increased by almost 10 times, its ethnic type has changed. In 1874, 45% of the Crimeans were Great Russians and Little Russians, about 35% were Crimean Tatars.

Greeks, Germans and Bulgarians come here en masse. In 1784, a military fortress was laid, which was destined to play a prominent role in the history of the Crimea and Russia as a whole. Roads are being built everywhere. Active cultivation of grapes contributes to the development of winemaking. The southern coast is becoming more and more popular among the nobility. turns into a resort town. For a hundred years, the population of the Crimean peninsula has increased by almost 10 times, its ethnic type has changed. In 1874, 45% of the Crimeans were Great Russians and Little Russians, about 35% were Crimean Tatars.

The dominance of the Russians in the Black Sea seriously disturbed a number of European countries. A coalition of decrepit Ottoman Empire, Great Britain, Austria, Sardinia and France unleashed. Command errors that caused the defeat in the battle on, the lag in technical equipment armies led to the fact that despite the unparalleled heroism of the defenders, shown during the year-long siege, Sevastopol was taken by the allies. After the end of the conflict, the city was returned to Russia in exchange for a number of concessions.

A lot happened during the Civil War in Crimea tragic events reflected in history. Since the spring of 1918, German and French expeditionary corps have been operating here, supported by the Tatars. The puppet government of Solomon Samoilovich of Crimea was replaced by the military power of Denikin and Wrangel. Only the troops of the Red Army managed to take control of the peninsular perimeter. After that, the so-called Red Terror began, as a result of which from 20 to 120 thousand people died.

In October 1921, the creation of the Autonomous Crimean Soviet Socialist Republic in the RSFSR was announced from the regions of the former Taurida province, renamed in 1946 into the Crimean region. The new government gave great attention her. The policy of industrialization led to the emergence of the Kamysh-Burun shipyard and, in the same place, a mining and processing plant was built, and in a metallurgical plant.

Further equipment was prevented by the Great Patriotic War. Already in August 1941, about 60 thousand ethnic Germans living on permanent basis, and in November, the Crimea was left by the Red Army. Only two centers of resistance to the Nazis remained on the peninsula - the Sevastopol fortified area and, but they also fell by the autumn of 1942. After the retreat Soviet troops partisan detachments began to actively operate here. The occupying authorities pursued a policy of genocide against "inferior" races. As a result, by the time of liberation from the Nazis, the population of Taurida had almost tripled.

Already in August 1941, about 60 thousand ethnic Germans living on permanent basis, and in November, the Crimea was left by the Red Army. Only two centers of resistance to the Nazis remained on the peninsula - the Sevastopol fortified area and, but they also fell by the autumn of 1942. After the retreat Soviet troops partisan detachments began to actively operate here. The occupying authorities pursued a policy of genocide against "inferior" races. As a result, by the time of liberation from the Nazis, the population of Taurida had almost tripled.

The invaders were expelled from here. After that, the facts of mass cooperation with the Nazis of the Crimean Tatars and representatives of some other national minorities were revealed. By decision of the USSR government, more than 183 thousand people of Crimean Tatar origin, a significant number of Bulgarians, Greeks and Armenians were forcibly deported to remote regions of the country. In 1954, the region was included in the Ukrainian SSR at the suggestion of N.S. Khrushchev.

The latest history of Crimea and our days

After the collapse of the USSR in 1991, Crimea remained in Ukraine, having received autonomy with the right to have its own constitution and president. After lengthy negotiations, the basic law of the republic was approved Verkhovna Rada. Yuri Meshkov became the first president of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea in 1992. Subsequently, relations between official Kyiv escalated. The Ukrainian parliament adopted in 1995 a decision to abolish the presidency on the peninsula, and in 1998  President Kuchma signed the Decree approving new constitution ARC, with the provisions of which not all the inhabitants of the republic agreed.

President Kuchma signed the Decree approving new constitution ARC, with the provisions of which not all the inhabitants of the republic agreed.

Internal contradictions, coinciding in time with serious political exacerbations between Ukraine and Russian Federation, in 2013 they split the society. One part of the inhabitants of Crimea was in favor of returning to the Russian Federation, the other part was in favor of staying in Ukraine. On this occasion, on March 16, 2014, a referendum was held. Most of the Crimeans who took part in the plebiscite voted for reunification with Russia.

Back in the days of the USSR, many were built on Taurida, which was considered an all-Union health resort. had no analogues in the world at all. The development of the region as a resort continued both in the Ukrainian period of the history of Crimea and in the Russian one. Despite all the interstate contradictions, it still remains a favorite vacation spot for both Russians and Ukrainians. This land is infinitely beautiful and ready to welcome guests from any country in the world! We offer in conclusion documentary, pleasant viewing!

CHAPTER 13. CRIMEA AS A PART OF THE RUSSIAN EMPIRE. XVIII–XIX CENTURIES

By decree of Emperor Alexander I of October 8, 1802, the Novorossiysk province was divided into Nikolaev, Ekaterinoslav and Taurida. Entered the Tauride province Crimean peninsula, Dneprovsky, Melitopol and Fanagorisky districts of the Novorossiysk province. At the same time, the Phanagoria district was renamed Tmutarakansky, and in 1820 it was transferred to the administration of the Caucasus region. In 1837, Yalta uyezd appeared in Crimea, separated from Simferopol uyezd.

The main occupation of the Crimean Tatars on the peninsula in early XIX century was cattle breeding. They raised horses, cows, oxen, goats and sheep. Farming was a secondary activity. Horticulture, beekeeping and viticulture flourished in the foothills and by the sea. Crimean honey in large quantities exported from the country, especially to Turkey. Due to the fact that the Karan forbids Muslims to drink wine, in the Crimea, mainly table grapes were bred. In 1804 in Sudak, and in 1828 in Magarach near Yalta, state-owned educational establishments winemaking and viticulture. Several decrees were issued providing benefits to persons engaged in horticulture and viticulture, they were transferred free of charge to hereditary possession of state lands. In 1848, 716,000 buckets of wine were produced in the Crimea. A large amount of wool from fine-fleeced sheep was exported. towards the middle 19th century in the Crimea there were twelve cloth factories. At the same time, the production of grain and tobacco increased significantly. In the first half of the 19th century, from 5 to 15 million poods of salt were mined annually in the Crimea, which was exported both to the interior of the Russian Empire and abroad. Up to 12 million poods of red fish were also exported annually. The study of Crimean minerals began. By 1828, there were 64 manufacturing enterprises on the Crimean peninsula, by 1849 - 114. Crimean moroccos were especially valued. Warships were built at the largest state-owned shipyards in Sevastopol. At the private shipyards of Yalta, Alushta, Miskhor, Gurzuf, Feodosia, merchant and small ships for coastal navigation were built.

In 1811, the Feodosia Historical Museum was opened, in 1825 - the Kerch Historical Museum. In 1812, a men's gymnasium was opened in Simferopol. In the same year, the botanist Khristian Khristianovich Steven founded the Nikitsky Botanical Garden on the southern coast of the Crimea near the village of Nikita.

At the beginning of the 19th century, people traveled to the Crimea from Moscow along the Volga to Tsaritsyn, the Don to Rostov, the Sea of Azov to Kerch. In 1826, a road was built from Simferopol to Alushta, in 1837 it was extended to Yalta, and in 1848 to Sevastopol. In 1848, on the border of the southern coast of Crimea and the northern slope of the mountains, the Baidar Gates were built.

The reference book of the Central Statistical Committee of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of 1865 "Lists of populated places of the Russian Empire - Taurida Governorate" outlines the beginning of the history of Crimea as part of the Russian Empire:

“On the peninsula, the administration had even more worries, it was necessary to arrange cities that were ruined or fell into decay during his subordination, populate the villages and form Russian citizens from the Tatars. The fact that at the end of the last century there were only 900 houses in Yevpatoria, 1500 in Bakhchisarai, and in Karasubazar instead of the previous 6000 there were slightly more than 2000 speaks clearly about the decline of cities. About Feodosia, when it was established by the city government, in 1803, the government itself expressed that "this city from a flourishing state, even under Turkish rule, now exists by one, so to speak, name." All cities in general received significant benefits. Ports were established in Feodosia, Evpatoria and Kerch, and foreign settlers were called here to develop trade, most of whom belonged to the Greeks. Simultaneously with the establishment of the port in Kerch, in 1821, the Kerch-Yenikol city government was formed, and Feodosiya was closed in 1829. Sevastopol, classified in 1826 as a first-class fortress, was an exclusively naval city and did not directly produce foreign trade. Bakhchisaray remained a purely Tatar city, Stary Krym - Armenian. Karasubazar also has an Asian type, but here the Tatars live together with the Armenians and Karaites; Finally, Simferopol, as a center of government, became a real rallying point for all the nationalities inhabiting the province.

The number of settlers in the settlements was insignificant. The first rural settlers on the peninsula, formed by the government, include the settlement in Balaklava and its environs of the Greeks, who are in the Albanian army. This army, under the name of the Greek, was formed in 1769, at the call of Count Orlov, who commanded our fleet in the Mediterranean, from the archipelago Greeks and acted together with the squadron against the Turks. At the conclusion of the Kuchuk-Kainarji peace, the archipelagos were resettled in Kerch, Yenikale and Taganrog, and after the subjugation of the peninsula, they were transferred, by order of Potemkin, to the above places to supervise the southern coast, from Sevastopol to Feodosia and protect it; during the second Turkish war, these Greeks mainly contributed to the pacification of the mountain Tatars.

As for the distribution of lands to Russian owners, at first it was carried out without any order, and no attention was paid to the fact that many of the new owners, having received lands, left them to their fate, moreover, the boundaries between the poieshchi lands were not precisely defined and Tatar, which caused a huge number of lawsuits. The obligations of the Tatars for the use of the landlords' lands were still insignificant: they usually consisted of a tithe from bread and hay and serving several days a year in favor of the landowner. Government taxes were assigned small, and the Tatars, along with the Armenians, Karaites and Greeks, were exempted from recruitment.

Russian settlements were originally based either near cities or on the routes between them. But in general there were not many Russian villages, and the number of our settlers on the peninsula, by the time of the Crimean War, was no more than 15,000 of both sexes. Simultaneously with the establishment of German colonies on the mainland, the Germans also appeared in the Crimea. In 1805, they formed three colonies in the Simferopol district: Neyzats, Friedenthal and Rosenthal, and three in Feodosiya: Geilbrun, Sudak and Herzenberg. At the same time, three Bulgarian colonies arose: Balta-Chokrak in the Simferopol district, Kyshlav and Stary Krym in Feodosia. All the colonies settled on good lands and, thanks to the industriousness of the settlers, they reached a flourishing position.

The arrangement of the southern coast, the construction of a highway along it, dates back to the 30s, by the time of the governor-general of Prince Vorontsov, who constantly took care to revive the region and introduce a proper economy in it. Due to the large settlement of the southern coast, in 1838 the Yalta district was formed here and Yalta turned from a village into a city.

In the late fifties and early sixties, the eviction (Tatars - A.A.) took on enormous proportions: the Tatars simply fled to the Turks in droves, abandoning their household. By 1863, when the eviction ended, the figure of those who left the peninsula extended, according to the local statistical committee, to 141,667 of both sexes; as in the first departure of the Tatars, the majority belonged to the mountainous, so now only the steppes were evicted almost exclusively. The reasons for this departure have not yet been sufficiently clarified, it remains only to note that there were some revived hopes for Turkey, which were partly religious in nature and at the same time a false fear that the Tatars would be persecuted for their course of action during the war.

Simultaneously with this eviction, the Ministry of State Property issued a challenge to the state peasants of the inner provinces to resettle in the Tauride Territory, and here were also Bulgarians from part of Bessarabia that had ceded to Moldavia, according to the Paris Treaty, and Little Russians and Great Russians from Moldavia and the northeastern part of Turkey. New settlers settled, both on empty state lands and on redundant plots of old Russian villages; this resettlement began in 1858 itself. By the beginning of 1863, according to the Ministry of State Property, there were only 29,246 Russian settlers of state peasants in the inner provinces in the province. By 1863, there were only 7,797 of both sexes in the province. Bulgarians resettled 17704 of both sexes. At the same time, Czechs from Bohemia settled in the three colonies of the Perekop district, among only 615 of both sexes. The population of the Taurida province at the beginning of 1864 consisted of 303,001 males and 272,350 females, and a total of 575,351 of both sexes, living in 2006 settlements with 89,775 households. In 1863, there were cities in the Taurida province: provincial Simferopol, Bakhchisaray, Karasubazar, county town Dnieper district of Aleshki, county town of Berdyansk, Nogaysk, Orekhov, county town of Evpatoria, county towns of Melitopol and Perekop, Armenian Bazaar, county town of Yalta, Balaklava, county town of Feodosia, Stary Krym, Sevastopol, Kerch and Yenikale. Counties - Simferopol, Berdyansk, Dnieper, Evpatoria, Melitopol, Perekop, Yalta, Feodosia and Kerch-Yenikol. 85,702 of both sexes live in the cities of the peninsula, 111,171 live in the counties. In total, 196,873 of both sexes live on the peninsula.

In the Crimean steppe, most of all they are engaged in breeding simple or thick-haired sheep and dragging salt from lakes, which is main subject holidays from the province into Russia. On the northern slope of the mountains, economic activity is concentrated on horticulture and winemaking, and, finally, on the southern coast, winemaking positively dominates, behind which the main place belongs to the cultivation of walnuts, which we call walnuts. The best wines are made on the southern coast, from Alushta to Laspi. The number of varieties of Crimean grapes is very large. of no small importance is also the sale of the grape itself, which goes like wine, for the most part to Moscow and Kharkov, mainly Crimean apples and pears are brought here.

The development of the Crimean peninsula was suspended by the Crimean, or as it was called in Europe, the Eastern War.

In 1853 Russian emperor Nicholas I proposed to Great Britain to divide the possessions of a weakened Turkey. Having been refused, he decided to seize the Black Sea straits of the Bosporus and the Dardanelles himself. The Russian Empire declared war on Turkey.

On November 18, 1853, the Russian squadron of Admiral Pavel Nakhimov destroyed the Turkish fleet in the Sinop Bay. This served as an excuse for England and France to enter their squadrons into the Black Sea and declare war on Russia. The allies - England and France - landed a landing force in the amount of sixty thousand people in the Crimea, near Yevpatoria and, after the battle on the Alma River with the thirty thousandth Russian army of A.S. backwardness of the Nikolaev Empire, despite the traditional heroism of the Russian soldier, approached Sevastopol - the main base of the Russian fleet on the Black Sea. The land army went to Bakhchisaray, leaving Sevastopol face to face with the allied expeditionary corps.

Having flooded the obsolete sailing ships and thus securing the city from the sea, the owners of which were the English and French steamboats, who did not need sails, and removing twenty-two thousand sailors from Russian ships, Admirals Kornilov and Nakhimov with the military engineer Totleben were able to surround Sevastopol with earthen fortifications and bastions within two weeks .

After a three-day bombardment of Sevastopol on October 5-7, 1854, the Anglo-French troops proceeded to the siege of the city, which lasted almost a year, until August 17, 1855, when, having lost admirals Kornilov, Istomin, Nakhimov, leaving Malakhov Kurgan, which was the dominant position over Sevastopol, the remnants of a twenty-two thousandth The Russian garrison, blowing up the bastions, went to the northern side of the Sevastopol Bay, reducing the Anglo-French expeditionary force, which was constantly receiving reinforcements, by seventy-three thousand people.

On March 17, 1856, a peace treaty was signed in Paris, according to which, thanks to disagreements between England and France, which facilitated the task of Russian diplomacy, Russia lost only the Danube Delta, Southern Bessarabia and the right to maintain a fleet on the Black Sea. After the defeat of France in the war with Bismarck's Germany in 1871, the Russian Empire canceled the humiliating articles of the Treaty of Paris, which forbade it to maintain a fleet and fortifications on the Black Sea.

As a result of the Crimean War, the peninsula fell into disrepair, more than three hundred destroyed villages were abandoned by the population.

In 1874, a railway was laid from Aleksandrovsk (now Zaporozhye) to Somferopol, which continued to Sevastopol. In 1892, movement began along the Dzhankoy-Kerch railway, which led to a significant acceleration of the economic development of the Crimea. By the beginning of the 20th century, 25 million poods of grain were exported from the Crimean peninsula annually. At the same time, especially after the royal family bought Livadia in 1860, Crimea turned into a resort peninsula. On the southern coast of Crimea, the highest Russian nobility began to rest, for which magnificent palaces were built in Massandra, Livadia, Miskhor.

Viticulture, winemaking, fruit growing, tobacco growing, livestock breeding (cattle breeding, sheep breeding, horse breeding, astrakhan breeding, beekeeping), sericulture, and essential oil crops were traditionally developed in Crimea. Agriculture became the predominant occupation of the Crimean population. By the 1890s, grain crops occupied 220,000 acres of land. Orchards and vineyards each occupied 5,000 acres. Half of the Crimean land was owned by landlords, 10% - peasant communities, 10% - peasant owners, the rest of the land belonged to the state and the church.

In the second half of the 18th century, systematic archaeological research was widely developed in the Crimea. In 1871, on the initiative of N.N. Miklukho-Maclay, a research biological station was established in Sevastopol.

According to the 1897 census, 186,000 Crimean Tatars lived in Crimea. total population peninsula reached half a million people living in twelve cities and 2500 settlements.

By the end of the 19th century, the Taurida province consisted of Berdyansk, Dnieper, Perekop, Simferopol, Feodosia and Yalta counties. The center of the province was the city of Simferopol.

From the book History of Crimea author Andreev Alexander RadievichChapter 13. CRIMEA AS A PART OF THE RUSSIAN EMPIRE. XVIII - XIX centuries. By decree of Emperor Alexander I of October 8, 1802, the Novorossiysk province was divided into Nikolaev, Yekaterinoslav and Taurida. The Taurida province included the Crimean peninsula, the Dnieper,

From the book History of Russia from the beginning of the XVIII to late XIX century author Bokhanov Alexander NikolaevichChapter 15. The foreign policy of the Russian Empire in the second half of the 18th century Panin and the Dissident Question in Poland The accession to the throne of Catherine II changed little in the main directions of Russia's foreign policy. They essentially remained

From book The World History: in 6 volumes. Volume 4: The World in the 18th Century author Team of authorsCENTER AND PERIPHERY IN THE POLITICS OF THE RUSSIAN EMPIRE OF THE XVIII CENTURY. FORMATION OF THE BASES OF NATIONAL POLICY By the end of the XVII century. territorially administrative structure Russia and its corresponding management system individual regions countries were heterogeneous.

From the book Shadow People author Prokhozhev Alexander AlexandrovichChapter II. JEWS IN THE RUSSIAN EMPIRE

From the book Confession, Empire, Nation. Religion and the Problem of Diversity in the History of the Post-Soviet Space author Semenov AlexanderLyudmila Posokhova Orthodox collegiums of the Russian Empire (second half of the 18th - early 19th centuries): between traditions and innovations

From the book From the history of dentistry, or Who treated the teeth Russian monarchs author Zimin Igor ViktorovichChapter 3 Dentistry in the Russian Empire in the XVIII century At the turn of the XVII-XVIII centuries. Russia begins a political, economic and cultural "drift" towards Europe, as a result of which a stream of specialists who worked in various fields poured into the Moscow kingdom. There were

author Andreev Alexander RadievichUkraine as part of the Russian Empire Absorption of the Hetmanate by the Russian Empire continued until late XVII I century. Battle of Poltava long years determined the political future of Ukraine. Volyn and Galicia remained under Poland, Kyiv and the Left Bank - under Russia, southern Ukraine

From the book Terra incognita [Russia, Ukraine, Belarus and their political history] author Andreev Alexander RadievichBelarus as part of the Russian Empire The attempts of the Radziwills and Sapiehas to create an independent Grand Duchy of Lithuania were not completed. Throughout the 17th and early 18th centuries Belarusian lands hostilities and large-scale wars were fought. The population of the Principality from three

From the book History of Ukraine. South Russian lands from the first Kyiv princes to Joseph Stalin author Allen William Edward DavidChapter 5 Ukrainian land within the Russian Empire

From the book Russian Empire in Comparative Perspective author History Team of authors --Andreas Kappeler Formation of the Russian Empire in the 15th - early 18th centuries: the legacy of Russia, Byzantium and the Horde

From the book History of Ukraine author Team of authorsUkraine as part of the Russian Empire After the final liquidation of the Ukrainian Hetmanate, at the beginning of the 19th century. the new administrative structure of Ukraine was completed. It was divided into nine provinces, which formed three regions: the Left Bank (consisting of

From the book Nobility, power and society in provincial Russia of the 18th century author Team of authorsElena Nigmetovna Marasinova. "Adventures in the Light": Episodes Everyday life provincial nobleman second half of XVIII century (according to the Complete Collection of Laws of the Russian Empire) "Province", "village", "estate" In the second half of the XVIII century, the concept

From the book History of the Philippines [ Brief essay] author Levtonova Yulia OlegovnaChapter V PHILIPPINES AS PART OF THE SPANISH EMPIRE (XVII-XVIII centuries) FEATURES OF THE SPANISH COLONIAL POLICY IN THE XVII-XVIII centuries Spain lost its former maritime and colonial power and turned into a minor European power. While the advanced countries of Western

From the book Secret Archives of Russian Freemasons author Sokolovskaya Tira OttovnaSIGNS OF THE MASONIC LODGES OF THE RUSSIAN EMPIRE of the second half of the 18th - the first quarter of the 19th century The reference list below is provided with illustrations - schematic images of the signs. The signs are arranged in chronological order. If opening dates are known and

From the book The Baltic States on the Fracture of International Rivalry. From the invasion of the Crusaders to the Peace of Tartu in 1920 author Vorobieva Lyubov MikhailovnaChapter V. Estonia and Livonia as part of the Russian Empire: between a German baron and a Russian

From the book Islam in Abkhazia (A look through history) author Tatyrba AdamII. The Abkhaz principality within the Russian Empire The tragedy of Keleshbey Chachba The end of the 18th century. was marked by the coming to power in Abkhazia to replace the rulers from the Chachba (Shervashidze) clan Manuchar (Suleimanbey, 1757–1770), Zurab (Surabbey, 1770–1779) and Levan (Muhammadbey, 1779–1789) a new

Chapter 13. CRIMEA AS A PART OF THE RUSSIAN EMPIRE. XVIII-XIX CENTURY.

By decree of Emperor Alexander I of October 8, 1802, the Novorossiysk province was divided into Nikolaev, Yekaterinoslav and Taurida. The Tauride province included the Crimean peninsula, the Dnieper, Melitopol and Fanagoria districts of the Novorossiysk province. At the same time, the Fanagoriye district was renamed Tmutarakansky, and in 1820 it was transferred to the administration of the Caucasus region. In 1837, Yalta uyezd appeared in Crimea, separated from Simferopol uyezd.

The main occupation of the Crimean Tatars on the peninsula at the beginning of the 19th century was cattle breeding. They raised horses, cows, oxen, goats and sheep. Farming was a secondary activity. Horticulture, beekeeping and viticulture flourished in the foothills and by the sea. Crimean honey was exported in large quantities from the country, especially to Turkey. Due to the fact that the Koran forbids Muslims to drink wine, in the Crimea, mainly table grapes were bred. In 1804 in Sudak, and in 1828 in Magarach near Yalta, state educational institutions of winemaking and viticulture were opened. Several decrees were issued that provided benefits to persons engaged in horticulture and viticulture, they were transferred free of charge to hereditary possession of state lands. In 1848, 716,000 buckets of wine were produced in the Crimea. A large amount of wool from fine-fleeced sheep was exported. To mid-nineteenth century in the Crimea, there were twelve cloth factories. At the same time, the production of grain and tobacco increased significantly. In the first half of the 19th century, from 5 to 15 million poods of salt were mined annually in the Crimea, which was exported both to the interior of the Russian Empire and abroad. Up to 12 million poods of red fish were also exported annually. The study of Crimean minerals began. By 1828, there were 64 manufacturing enterprises on the Crimean peninsula, by 1849 - 114. Crimean moroccos were especially valued. Warships were built at the largest state-owned shipyards in Sevastopol. At the private shipyards of Yalta, Alushta, Miskhor, Gurzuf, Feodosia, merchant and small ships for coastal navigation were built.

In 1811, the Feodosia Historical Museum was opened, in 1825 - the Kerch Historical Museum. In 1812, a men's gymnasium was opened in Simferopol. In the same year, the Nikitsky Botanical Garden was founded by the botanist Christian Khristianovich Steven on the southern coast of Crimea near the village of Nikita.

At the beginning of the 19th century, people traveled to the Crimea from Moscow along the Volga to Tsaritsyn, the Don to Rostov, the Sea of Azov to Kerch. In 1826 a road was built from Simferopol to Alushta, in 1837 it was extended to Yalta, and in 1848 to Sevastopol. In 1848, on the border of the southern coast of Crimea and the northern slope of the mountains, the Baidar Gates were built.

Museum of Totleben in Sevastopol

The reference book of the Central Statistical Committee of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of 1865 "Lists of populated places of the Russian Empire - Taurida Governorate" outlines the beginning of the history of Crimea as part of the Russian Empire:

“On the peninsula, the administration had even more worries, it was necessary to arrange cities that were ruined or fell into decay during his subordination, populate the villages and form Russian citizens from the Tatars. The fact that at the end of the last century there were only 900 houses in Yevpatoria, 1500 in Bakhchisarai, and in Karasubazar instead of the previous 6000 there were slightly more than 2000 speaks clearly about the decline of cities. About Feodosia, when it was established by the city government, in 1803, the government itself expressed that "this city from a flourishing state, even under Turkish rule, now exists by one, so to speak, name." All cities in general received significant benefits. Ports were established in Feodosia, Evpatoria and Kerch, and foreign settlers were called here to develop trade, most of whom belonged to the Greeks. Simultaneously with the establishment of the port in Kerch, in 1821, the Kerch-Yenikol city government was formed, and Feodosiya was closed in 1829. Sevastopol, classified in 1826 as a first-class fortress, was an exclusively naval city and did not directly produce foreign trade. Bakhchisaray remained a purely Tatar city, Stary Krym - Armenian. Karasubazar also has an Asian type, but here the Tatars live together with the Armenians and Karaites; Finally, Simferopol, as a center of government, became a real rallying point for all the nationalities inhabiting the province.

The number of settlers in the settlements was insignificant. The first rural settlers on the peninsula, formed by the government, include the settlement in Balaklava and its environs of the Greeks, who are in the Albanian army. This army, under the name of the Greek, was formed in 1769, at the call of Count Orlov, who commanded our fleet in the Mediterranean, from the archipelago Greeks and acted together with the squadron against the Turks. At the conclusion of the Kuchuk-Kainarji peace, the archipelagos were resettled in Kerch, Yenikale and Taganrog, and after the subjugation of the peninsula, they were transferred, by order of Potemkin, to the above places to supervise the southern coast, from Sevastopol to Feodosia and protect it; during the second Turkish war, these Greeks mainly contributed to the pacification of the mountain Tatars.

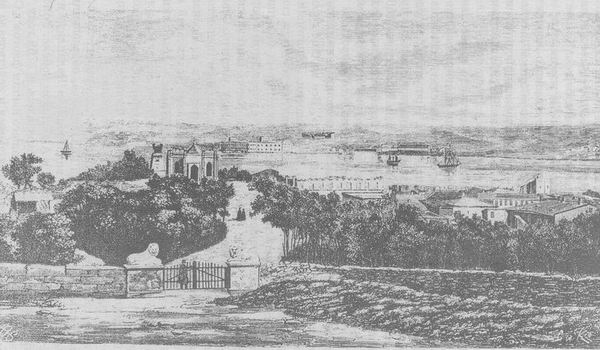

South side of Sevastopol, boulevard and monument to Kazarsky

As for the distribution of land to Russian owners, at first it was carried out without any order, and no attention was paid to the fact that many of the new owners, having received land, left them to their fate, moreover, the boundaries between the landlords' lands were not precisely defined. and Tatar, which caused a huge number of lawsuits. The obligations of the Tatars for the use of the landlords' lands were still insignificant: they usually consisted of a tithe from bread and hay and serving several days a year in favor of the landowner. Government taxes were assigned small, and the Tatars, along with the Armenians, Karaites and Greeks, were exempted from recruitment.

Russian settlements were originally based either near cities or on the routes between them. But in general there were not many Russian villages, and the number of our settlers on the peninsula, by the time of the Crimean War, was no more than 15,000 of both sexes. Simultaneously with the establishment of German colonies on the mainland, the Germans also appeared in the Crimea. In 1805, they formed three colonies in the Simferopol district: Neyzats, Friedenthal and Rosenthal, and three in Feodosiya: Geilbrun, Sudak and Herzenberg. At the same time, three Bulgarian colonies arose: Balta-Chokrak in the Simferopol district, Kyshlav and Stary Krym in Feodosia. All the colonies settled down on good lands and, thanks to the industriousness of the settlers, reached a flourishing position.

The arrangement of the southern coast, the construction of a highway along it, dates back to the 30s, by the time of the governor-general of Prince Vorontsov, who constantly took care to revive the region and introduce a proper economy in it. Due to the large settlement of the southern coast, in 1838 the Yalta district was formed here and Yalta turned from a village into a city.

In the late fifties and early sixties, eviction (Tatars - A.A.) took on enormous proportions: the Tatars simply fled to the Turks in masses, abandoning their economy. By 1863, when the eviction ended, the figure of those who left the peninsula extended, according to the local statistical committee, to 141,667 of both sexes; as in the first departure of the Tatars, the majority belonged to the mountainous, so now only the steppes were evicted almost exclusively. The reasons for this departure are not yet sufficiently clear, it remains only to note that there were some revived hopes for Turkey, which were partly religious in nature and at the same time a false fear that the Tatars would be persecuted for their course of action during the war.

Simultaneously with this eviction, the Ministry of State Property issued a challenge to the state peasants of the inner provinces to resettle in the Tauride Territory, and here were also Bulgarians from part of Bessarabia that had ceded to Moldavia, according to the Paris Treaty, and Little Russians and Great Russians from Moldavia and the northeastern part of Turkey. New settlers settled, both on empty state lands and on redundant plots of old Russian villages; this resettlement began in 1858 itself. By the beginning of 1863, according to the Ministry of State Property, there were only 29,246 Russian settlers of state peasants in the inner provinces in the province. By 1863, there were only 7,797 of both sexes in the province. Bulgarians resettled 17704 of both sexes. At the same time, Czechs from Bohemia settled in the three colonies of the Perekop district, among only 615 of both sexes. The population of the Taurida province at the beginning of 1864 consisted of 303,001 males and 272,350 females, and a total of 575,351 of both sexes, living in 2006 settlements with 89,775 households. In 1863, there were cities in the Tauride province: the provincial Simferopol, Bakhchisaray, Karasubazar, the county town of the Dnieper district of Alyoshki, the county town of Berdyansk, Nogaysk, Orekhov, the county town of Evpatoria, the county cities of Melitopol and Perekop, the Armenian Bazaar, the county town of Yalta, Balaklava, the county town of Feodosia , Stary Krym, Sevastopol, Kerch and Yenikale. Counties - Simferopol, Berdyansk, Dnieper, Evpatoria, Melitopol, Perekop, Yalta, Feodosia and Kerch-Yenikolsky. 85,702 of both sexes live in the cities of the peninsula, 111,171 live in the counties. In total, 196,873 of both sexes live on the peninsula.

The interior of the church near Sevastopol

In the Crimean steppe, most of all they are engaged in breeding simple or thick-haired sheep and dragging from salt lakes, which is the main subject of vacation from the province into Russia. On the northern slope of the mountains, economic activity is concentrated on horticulture and winemaking, and, finally, on the southern coast, winemaking positively dominates, behind which the main place belongs to the cultivation of walnuts, which we call walnuts. The best wines are made on the southern coast, from Alushta to Laspi. The number of varieties of Crimean grapes is very large, the sale of the grapes themselves is also of no small importance, which goes like wine, mostly to Moscow and Kharkov, mainly Crimean apples and pears are brought here.

The development of the Crimean peninsula was suspended by the Crimean, or as it was called in Europe, the Eastern War.

In 1853, the Russian Emperor Nicholas I proposed to Great Britain to divide the possessions of a weakened Turkey. Having been refused, he decided to seize the Black Sea straits of the Bosporus and the Dardanelles himself. The Russian Empire declared war on Turkey.

On November 18, 1853, the Russian squadron of Admiral Pavel Nakhimov destroyed the Turkish fleet in the Sinop Bay. This served as an excuse for England and France to enter their squadrons into the Black Sea and declare war on Russia. The allies - England and France - landed a landing in the amount of sixty thousand people in the Crimea, near Yevpatoriya and, after the battle on the Alma River with the thirty thousandth Russian army of A.S. backwardness of the Nikolaev Empire, despite the traditional heroism of the Russian soldier, approached Sevastopol - the main base of the Russian fleet on the Black Sea. The land army went to Bakhchisaray, leaving Sevastopol face to face with the allied expeditionary corps.

Boulevard and garden in Sevastopol

Sinop battle

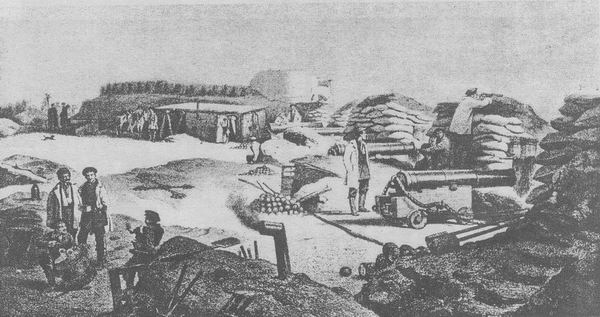

Interior view of one of the bastions of the Malakhov Kurgan

Having sunk obsolete sailing ships in the roadstead of Sevastopol and thus securing the city from the sea, the owners of which were the steamships of the British and French, who did not need sails, and removing twenty-two thousand sailors from Russian ships, Admirals Kornilov and Nakhimov with military engineer Totleben within two weeks were able to surround Sevastopol with earthen fortifications and bastions.

Monument on the grave of Russian soldiers in Sevastopol

After a three-day bombardment of Sevastopol on October 5 - 7, 1854, the Anglo-French troops proceeded to the siege of the city, which lasted for a year, until August 17, 1855, when, having lost Admirals Kornilov, Istomin, Nakhimov, leaving Malakhov Kurgan, which was the dominant position over Sevastopol, the remnants of the twenty-two thousandth The Russian garrison, blowing up the bastions, went to the northern side of the Sevastopol Bay, reducing the Anglo-French expeditionary force, which was constantly receiving reinforcements, by seventy-three thousand people.

On March 17, 1856, a peace treaty was signed in Paris, according to which, thanks to disagreements between England and France, which facilitated the task of Russian diplomacy, Russia lost only the Danube Delta, Southern Bessarabia and the right to maintain a fleet on the Black Sea. After the defeat of France in the war with Bismarck's Germany in 1871, the Russian Empire canceled the humiliating articles of the Treaty of Paris, which forbade it to maintain a fleet and fortifications on the Black Sea.

As a result of the Crimean War, the peninsula fell into disrepair, more than three hundred destroyed villages were abandoned by the population.

In 1874, a railway was laid from Aleksandrovsk (now Zaporozhye) to Simferopol, which continued to Sevastopol. In 1892, movement began along the Dzhankoy-Kerch railway, which led to a significant acceleration of the economic development of the Crimea. By the beginning of the 20th century, 25 million poods of grain were exported annually from the Crimean peninsula. At the same time, especially after the royal family bought Livadia in 1860, Crimea turned into a resort peninsula. On the southern coast of Crimea, the highest Russian nobility began to rest, for which magnificent palaces were built in Massandra, Livadia, Miskhor.

Viticulture, winemaking, fruit growing, tobacco growing, livestock breeding (cattle breeding, sheep breeding, horse breeding, astrakhan breeding, beekeeping), sericulture, and essential oil crops were traditionally developed in Crimea. Agriculture became the predominant occupation of the Crimean population. By the 1890s, grain crops occupied 220,000 acres of land. Orchards and vineyards each occupied 5,000 acres. Half of the Crimean land was owned by the landowners, 10% - by peasant communities, 10% - by peasant proprietors, the rest of the land belonged to the state and the church.

Simferopol and the pass through Yalta

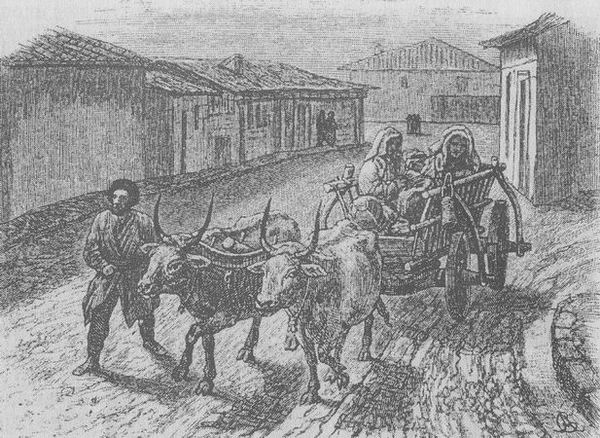

Chumatskaya ride

Chumatskaya team

In the second half of the 18th century, systematic archaeological research was widely developed in the Crimea. In 1871, on the initiative of H. H. Miklukho-Maclay, a research biological station was established in Sevastopol.

According to the 1897 census, 186,000 Crimean Tatars lived in Crimea. The total population of the peninsula reached half a million people living in twelve cities and 2500 settlements.

By the end of the 19th century, the Taurida province consisted of Berdyansk, Dnieper, Perekop, Simferopol, Feodosia and Yalta counties. The center of the province was the city of Simferopol.

"On the watchdog Moscow border" by Sergei Ivanov. Photo: rus-artist.ru

How the peninsula was annexed to the Russian Empire under Catherine II

"Like the king of the Crimea came to our land ..."

The first raid of the Crimean Tatars for slaves on the lands of Moscow Rus took place in 1507. Before that, the lands of Muscovy and the Crimean Khanate separated the Russian and Ukrainian territories of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, so Muscovites and Krymchaks even sometimes united against the Litvins, who dominated the entire 15th century in Eastern Europe.

In 1511-1512, the "Crimeans", as the Russian chronicles called them, ravaged the Ryazan land twice, and the next year Bryansk. Two years later, two new ruins of the environs of Kasimov and Ryazan were committed with the mass removal of the population into slavery. In 1517 - a raid on Tula, and in 1521 - the first raid of the Tatars on Moscow, the ruin of the environs and the withdrawal of many thousands into slavery. Six years later, the next big raid on Moscow. The crown of the Crimean raids on Russia is 1571, when Khan Giray burned Moscow, plundered more than 30 Russian cities and took about 60 thousand people into slavery.

As one of the Russian chroniclers wrote: “Weigh, father, this real misfortune is upon us, as the king of the Crimea has come to our land, to the river Oka on the shore, gather many hordes with you.” In the summer of 1572, 50 kilometers south of Moscow, a fierce battle took place at Molodi for four days - one of the largest battles in the history of Muscovite Russia, when Russian army with great difficulty defeated the army of the Crimea.

During the Time of Troubles, the Crimeans almost every year made major raids on Russian lands, they continued throughout the 17th century. For example, in 1659, Crimean Tatars near Yelets, Kursk, Voronezh and Tula burned 4,674 houses and drove 25,448 people into slavery.

By the end of the 17th century, the confrontation shifted to the south of Ukraine, closer to the Crimea. For the first time, the Russian armies are trying to directly attack the peninsula itself, which for almost two centuries, since the time of the Lithuanian raids on the Crimea, did not know foreign invasions and was a safe haven for slave traders. However, the XVIII century is not complete without Tatar raids. For example, in 1713, the Crimeans plundered the Kazan and Voronezh provinces, and the following year, the environs of Tsaritsyn. A year later - Tambov.

It is significant that the last raid with the mass removal of people into slavery took place just fourteen years before the annexation of Crimea to Russia - the Crimean Tatar "horde" in 1769 devastated the Slavic settlements between modern Kirovograd and Kherson.

The Tatar population of Crimea actually lived by subsistence agriculture, professed Islam and was not taxed. The economy of the Crimean Khanate for several centuries consisted of taxes collected from the non-Tatar population of the peninsula - the trade and craft population of the Khanate was exclusively Greeks, Armenians and Karaites. But the main source of excess income for the Crimean nobility was the "raid economy" - the capture of slaves in Eastern Europe and their resale to the Mediterranean regions. As a Turkish official explained to a Russian diplomat in the middle of the 18th century: “There are more than a hundred thousand Tatars who have neither agriculture nor trade: if they don’t raid, then what will they live on?”

Tatar Kafa - modern Feodosia - was one of the largest slave markets of that time. For four centuries, from a few thousand to - after the most "successful" raids - several tens of thousands of people were sold here annually as a living commodity.

“Crimean Tatars will never be useful subjects”

Russia launched a counteroffensive from the end of the 17th century, when the first Crimean campaigns of Prince Golitsyn followed. The archers with the Cossacks reached the Crimea on the second attempt, but they did not overcome Perekop. For the first time, the Russians avenged the burning of Moscow only in 1736, when the troops of Field Marshal Munnich broke through Perekop and captured Bakhchisarai. But then the Russians could not stay in the Crimea because of the epidemics and opposition from Turkey.

"A line of sight. Southern Frontier" by Maximilian Presnyakov. Source: runivers.ru

By the beginning of the reign of Catherine II, the Crimean Khanate did not represent military threat, but remained a problematic neighbor as an autonomous part of the mighty Ottoman Empire. It is no coincidence that the first report on Crimean issues for Catherine was prepared exactly one week after she ascended the throne as a result of a successful coup.

On July 6, 1762, Chancellor Mikhail Vorontsov presented a report “On Little Tataria”. About the Crimean Tatars, it said the following: “They are very prone to kidnapping and villainy ... they caused sensitive harm and insults to Russia by frequent raids, captivity of many thousands of inhabitants, driving away livestock and robbery.” And emphasized key value Crimea: “The peninsula is so important with its location that it can really be considered the key of Russian and Turkish possessions; as long as he remains in Turkish citizenship, he will always be terrible for Russia.

The discussion of the Crimean issue continued in the midst of Russian-Turkish war 1768-1774. Then the actual government of the Russian Empire was the so-called Council at the highest court. On March 15, 1770, at a meeting of the Council, the question of the annexation of Crimea was considered. Companions of Empress Catherine reasoned that "the Crimean Tatars, by their nature and position, will never be useful subjects," moreover, "no decent taxes can be collected from them."

But the Council eventually made a cautious decision not to annex Crimea to Russia, but to try to isolate it from Turkey. “By such immediate allegiance, Russia will arouse against itself a general and not unfounded envy and suspicion of the boundless intention of multiplying its regions,” the Council’s decision on a possible international reaction was said.

France was Turkey's main ally - it was her actions that were feared in St. Petersburg.

In her letter to General Pyotr Panin dated April 2, 1770, Empress Catherine summarized: “It is not at all our intention to have this peninsula and Tatar hordes, belonging to it, in our citizenship, and it is only desirable that they break away from Turkish citizenship and remain forever independent ... The Tatars will never be useful to our empire.

In addition to the independence of Crimea from the Ottoman Empire, Catherine's government planned to get the consent of the Crimean Khan to grant Russia the right to have military bases in Crimea. At the same time, the government of Catherine II took into account such a subtlety that all the main fortresses and the best harbors on the southern coast of Crimea belonged not to the Tatars, but to the Turks - and in which case the Tatars were not too sorry to give the Russians Turkish possessions.

For a year, Russian diplomats tried to convince the Crimean Khan and his sofa (government) to declare independence from Istanbul. During the negotiations, the Tatars tried not to say yes or no. As a result, the Imperial Council in St. Petersburg, at a meeting on November 11, 1770, decided to "inflict strong pressure on the Crimea, if the Tatars living on this peninsula still remain stubborn and do not stick to those who have already settled down from the Ottoman Port."

Fulfilling this decision of St. Petersburg, in the summer of 1771, troops under the command of Prince Dolgorukov entered the Crimea and inflicted two defeats on the troops of Khan Selim III.

Regarding the occupation of Kafa (Feodosia) and the termination of the largest slave market in Europe, Catherine II wrote to Voltaire in Paris on July 22, 1771: "If we took Kafa, the costs of the war are covered." Regarding the policy of the French government, which actively supported the Turks and Polish rebels who fought with Russia, Catherine, in a letter to Voltaire, deigned to joke to the whole of Europe: “In Constantinople, they are very sad about the loss of Crimea. We should send them a comic opera to dispel their sadness, and a puppet comedy to the Polish rebels; it would be more useful to them than the large number of officers that France sends to them.

"The most kind Tatar"

Under these conditions, the nobility of the Crimean Tatars preferred to temporarily forget about the Turkish patrons and quickly make peace with the Russians. On June 25, 1771, an assembly of beys, local officials and clergy signed a preliminary act on the obligation to declare the khanate independent from Turkey, and also to enter into an alliance with Russia, electing as a khan and kalgi(Khan's heir-deputy) loyal to Russia descendants of Genghis Khan - Sahib-Girey and Shagin-Girey. The former Khan fled to Turkey.

In the summer of 1772, peace negotiations began with the Ottomans, at which Russia demanded to recognize the independence of the Crimean Khanate. As an objection, the Turkish representatives spoke in the spirit that, having gained independence, the Tatars would begin to "do stupid things."

The Tatar government in Bakhchisarai tried to evade signing an agreement with Russia, waiting for the outcome of negotiations between the Russians and the Turks. At this time, an embassy arrived in St. Petersburg from the Crimea, headed by the Kalga Shagin-Giray.

The young prince was born in Turkey, but managed to travel around Europe, knew Italian and Greek. The Empress liked the representative of the Khan's Crimea. Catherine II described him in a very feminine way in a letter to one of her friends: “We have a Kalga Sultan here, a clan of the Crimean Dauphin. This, I think, is the most amiable Tatar one can find: he is handsome, smart, more educated than these people generally are; writes poems; he is only 25 years old; he wants to see and know everything; everyone loved him."

In St. Petersburg, a descendant of Genghis Khan continued and deepened his passion for modern European art and theater, but this did not strengthen his popularity among the Crimean Tatars.

By the autumn of 1772, the Russians managed to crush Bakhchisaray, and on November 1, an agreement was signed between the Russian Empire and the Crimean Khanate. It recognized the independence of the Crimean Khan, his election without any participation of third countries, and also assigned to Russia the cities of Kerch and Yenikale with their harbors and adjacent lands.

However, the Imperial Council in St. Petersburg experienced some confusion when Vice Admiral Alexei Senyavin, who successfully commanded the Azov and Black Sea Fleet. He explained that neither Kerch nor Yenikale are convenient bases for the fleet and new ships cannot be built there. The best place for the base of the Russian fleet, according to Senyavin, was the Akhtiar harbor, now we know it as the harbor of Sevastopol.

Although the treaty with the Crimea had already been concluded, but luckily for St. Petersburg, the main treaty with the Turks had yet to be signed. And Russian diplomats hastened to include in it new demands for new harbors in the Crimea.

As a result, some concessions had to be made to the Turks, and in the text of the Kyuchuk-Kaynarji peace treaty of 1774, in the paragraph on the independence of the Tatars, the provision on the religious supremacy of Istanbul over the Crimea was nevertheless fixed - a requirement that was persistently put forward by the Turkish side.

For the still medieval society of the Crimean Tatars, religious primacy was weakly separated from administrative. The Turks, on the other hand, considered this clause of the treaty as a convenient tool for keeping Crimea in the orbit of their policy. Under these conditions, Catherine II seriously thought about the erection of the pro-Russian kalga Shagin-Giray to the Crimean throne.

However, the Imperial Council preferred to be cautious and decided that "by this change we could violate our agreements with the Tatars and give the Turks a reason to win them over to their side again." Sahib-Girey, the older brother of Shahin-Girey, remained Khan, ready to alternate between Russia and Turkey, depending on the circumstances.

At that moment, the Turks were brewing a war with Austria, and in Istanbul they hastened not only to ratify the peace treaty with Russia, but also, in accordance with its requirements, to recognize the Crimean Khan elected under pressure from the Russian troops.

As stipulated by the Kuchuk-Kaynardzhi agreement, the Sultan sent his caliph blessing to Sahib-Giray. However, the arrival of the Turkish delegation, the purpose of which was to hand over to the khan the Sultan's "firman", confirmation of the rule, produced in the Crimean society reverse effect. The Tatars took the arrival of the Turkish ambassadors for another attempt by Istanbul to return the Crimea under their usual rule. As a result, the Tatar nobility forced Sahib-Girey to resign and quickly elected a new Khan, Davlet-Girey, who never hid his pro-Turkish orientation.

Petersburg was unpleasantly surprised by the coup and decided to stake on Shagin Giray.

In the meantime, the Turks suspended the withdrawal of their troops from the Crimea provided for by the peace treaty (their garrisons still remained in several mountain fortresses) and began to hint to Russian diplomats in Istanbul about the impossibility of the independent existence of the peninsula. Petersburg understood that the problem could not be solved by diplomatic pressure and indirect actions alone.

Having waited until the beginning of winter, when the transfer of troops across the Black Sea was difficult and in Bakhchisarai they could not count on ambulance from the Turks, the Russian troops concentrated at Perekop. Here they waited for the news of the election of Shagin-Girey, the Nogai Tatars, as khan. In January 1777, the corps of Prince Prozorovsky entered the Crimea, escorting Shagin Giray, the legitimate ruler of the Nogai Tatars.

The pro-Turkish Khan Davlet Giray was not going to give up, he gathered forty thousandth militia and set out from Bakhchisarai to meet the Russians. Here he tried to deceive Prozorovsky - he began negotiations with him and, in their midst, unexpectedly attacked the Russian troops. But the actual military leader of Prozorovsky's expedition was Alexander Suvorov. The future generalissimo repulsed the unexpected attack of the Tatars and defeated their militia.

Khan Davlet Giray. Source: segodnya.ua

Davlet Giray fled under the protection of the Ottoman garrison to Kafu, from where he sailed to Istanbul in the spring. Russian troops occupied Bakhchisaray without difficulty, and on March 28, 1777, the Crimean divan recognized Shagin Giray as Khan.

The Turkish sultan, as the head of the Muslims of the whole world, did not recognize Shagin as the Crimean Khan. But the young ruler enjoyed the full support of St. Petersburg. Under an agreement with Shagin-Giray, Russia, as compensation for its expenses, received income from the Crimean treasury from salt lakes, all taxes levied on local Christians, as well as harbors in Balaklava and Gezlev (now Evpatoria). In fact, the entire economy of Crimea came under Russian control.

"Crimean Peter I"

After spending most life in Europe and Russia, where he received an excellent modern education for those years, Shagin-Giray was very different from the entire upper class of his home country. Court flatterers in Bakhchisarai even began to call him "Crimean Peter I."

Khan Shagin began by creating a regular army. Prior to this, only the militia existed in the Crimea, which gathered in case of danger, or in preparation for the next raid for slaves. The role of the permanent army was played by the Turkish garrisons, but they were evacuated to Turkey after the conclusion of the Kyuchuk-Kaynarji peace treaty. Shagin-Giray conducted a population census and decided to take one warrior from every five Tatar houses, and these houses were supposed to supply the warrior with weapons, a horse and everything necessary. Such a costly measure for the population caused strong discontent and the new khan failed to create a large army, although he had a relatively combat-ready khan's guard.

Shagin is trying to move the capital of the state to the seaside Kafa (Feodosia), where construction begins grand palace. He introduces new system officials - following the example of Russia, a hierarchical service is created with a fixed salary issued from the khan's treasury, local officials are deprived of the ancient right to take exactions directly from the population.

The wider it unfolded reform activity"Crimean Peter I", the more the dissatisfaction of the aristocracy and the entire Tatar population with the new khan increased. At the same time, the Europeanized Khan Shahin Giray executed those suspected of disloyalty quite in an Asian way.

The young Khan was not alien to both Asian splendor and a penchant for European luxury - he ordered expensive art objects from Europe, invited fashionable artists from Italy. Such tastes shocked the Crimean Muslims. Rumors spread among the Tatars that Khan Shagin "sleeps on the bed, sits on a chair and does not pray due to the law."

Dissatisfaction with the reforms of the "Crimean Peter I" and the growing influence of St. Petersburg led to a mass uprising in the Crimea that broke out in October 1777.

The rebellion, which began among the newly recruited troops, instantly covered the entire Crimea. The Tatars, having gathered a militia, managed to destroy a large detachment of Russian light cavalry in the Bakhchisarai region. The Khan's guard went over to the side of the rebels. The uprising was led by the brothers Shagin Giray. One of them, who had previously been the leader of the Abkhazians and Adyghes, was elected by the rebels as the new Khan of Crimea.

“We must think about appropriating this peninsula”

The Russians reacted quickly and harshly. Field Marshal Rumyantsev insisted on the toughest measures against the rebellious Tatars in order to "feel the full weight of Russian weapons, and bring them to repentance." Among the measures to suppress the uprising were the actual concentration camps of the 18th century, when the Tatar population (mostly families of rebels) were herded into blockaded mountain valleys and kept there without a food supply.

The Turkish fleet appeared off the coast of Crimea. Frigates entered the Akhtiar harbor, delivering troops and a note of protest against the actions of Russian troops in the Crimea. The Sultan, in accordance with the Kyuchuk-Kainarji peace treaty, demanded the withdrawal of Russian troops from the independent Crimea. Neither the Russians nor the Turks were ready for a big war, but formally Turkish troops could be present in the Crimea, since there were Russian units there. Therefore, the Turks tried to land on the Crimean coast without the use of weapons, and the Russians also tried to prevent them from doing so without firing shots.

Here the troops of Suvorov were helped by chance. A plague epidemic broke out in Istanbul, and under the pretext of quarantine, the Russians announced that they could not let the Turks ashore. In the words of Suvorov himself, they were "refused with complete affection." The Turks were forced to depart back to the Bosphorus. So the Tatar rebels were left without the support of the Ottoman patrons.

After that, Shagin-Giray and the Russian units managed to quickly deal with the rebels. The defeat of the uprising was also facilitated by the disassembly that immediately began between the Tatar clans and the pretenders to the Khan's throne.

It was then that in St. Petersburg they seriously thought about the complete annexation of Crimea to Russia. A curious document appears in the office of Prince Potemkin - an anonymous "Reasoning of one Russian Patriot, about the wars with the Tatars, and about the methods that serve to stop them forever." In fact, this is an analytical report and a detailed 11-point accession plan. Many of them were put into practice in the coming decades. So, for example, in the third article of the "Reasoning" it is said about the need to provoke civil strife among the various Tatar clans. Indeed, since the mid-70s of the XVIII century in the Crimea and in the nomadic hordes around it, with the help of Russian agents, riots and strife have not stopped. The fifth article speaks of the desirability of evicting unreliable Tatars from Crimea. And after the annexation of Crimea, the tsarist government actually encouraged the movement of "muhajirs" - agitators for the resettlement of the Crimean Tatars to Turkey.

Plans for the settlement of the peninsula by Christian peoples (Article 9 of the "Reasoning") in the near future were implemented by Potemkin very actively: Bulgarians, Greeks, Germans, Armenians were invited, Russian peasants were resettled from interior areas empire. Found application in practice and paragraph number 10, which was supposed to return to the cities of Crimea their ancient Greek names. In the Crimea, already existing settlements were renamed (Kafa-Feodosia, Gezlev-Evpatoria, etc.); and all newly formed cities received Greek names.

In fact, the annexation of Crimea went according to plan, which is still preserved in the archives.

Soon after the suppression of the Tatar rebellion, Catherine wrote a letter to Field Marshal Rumyantsev in which she agreed with his proposals:

"The independence of the Tatars in the Crimea is unreliable for us, and we must think about appropriating this peninsula."CHAPTER 11. THE CRIMEAN PENINSULA IN THE 18TH CENTURY

In 1709, the remnants of the defeated Russian tsar Peter I in Poltava battle Swedish troops Charles XII and the Cossacks of the Ukrainian hetman Ivan Mazepa went through Perevolochna to Turkish possessions. The Swedish king Charles XII soon ended up in Istanbul, and Mazepa died in September 1709 in Bendery. The emigrant Cossacks chose the general clerk Philip Orlyk as hetman, who in 1710 signed an alliance treaty in the Crimea between the Cossacks subordinate to him and the Crimean Khan. According to this agreement, the Crimean Khanate recognized the independence of Ukraine and agreed not to stop the war with the Muscovite state without the consent of the hetman in exile Orlyk.

On November 9, 1710, the Turkish Sultan Ahmet III declared war on Russia. Turkey, in once more deceived by French diplomacy, who wanted to ease the position of Sweden after Poltava and force Russia to fight on two fronts, she gathered a huge army of 120,000 Turks and 100,000 Crimean and Nogai Tatars. The troops of the Crimean Khan Devlet Girey II and the Nogais with their Kuban sultan, the son of the Khan, went on a campaign against the Moscow state. The purpose of the campaign was to capture Voronezh and destroy its shipyards, but this was not possible. At Kharkov, the Tatars were met by Russian troops under the command of General Shidlovsky. The Tatars plundered the district, took prisoners and returned to the Crimea. On the next trip to Right-Bank Ukraine in the spring of 1711, the Cossacks of Orlik, the Cossacks with Kosh Kostya Gordienko, Polish troops Poniatowski and the Budzhatsky Horde led by the Sultan, the son of the Crimean Khan. The 50,000-strong army reached the White Church, but could not take the fortress and returned home.

After the battle of the two hundred thousandth Turkish-Tatar army with forty thousand Russians on the Prut River in July 1711, Russia and Turkey signed an agreement according to which Russia was supposed to return Azov to Turkey and tear down the cities of Taganrog, Kamenny Zaton and all other fortifications built after 1696 and "the royal ambassador will no longer be in Tsaregrad."

In 1717, the Tatars made a big raid on Ukrainian lands, in 1717 - to the Russians, reaching Tambov and Simbirsk. During these years, the Crimean Khanate sold up to 20,000 slaves annually. In Crimea, intrigues and unrest among the Tatar nobility continuously took place, for which the Crimean khans of Gaza Girey II and Saadet Girey III were removed. State functions in the Crimea, Turkey carried out, not interested in strengthening the khanate, it also contained fortresses, artillery, and a management apparatus.

In 1723, Mengli Girey II became the Crimean Khan. Having destroyed some of the rebellious beys and murzas and confiscated their property, the new khan lowered taxes for the "black people", which made it possible to somewhat stabilize the situation in the khanate. In 1730, the Crimean Khan Kaplan Giray managed to “take under his hand” part of the Cossacks, who agreed to this because of Russia’s refusal to accept them back after the Mazepa betrayal. However, this did not strengthen the khanate. The economic and military lag of the Crimean Khanate from other European powers was very significant.

This was especially evident during the Russian-Turkish war of 1735-1739.

In 1732, the troops of the Crimean Khan received an order from the Ottoman Porte to invade Persia, with which Turkey had been at war for several years. Shortest way from Crimea to Persia passed through Russian territory, along which Tatar troops constantly moved, violating, as they would say now, the territorial integrity of the Russian Empire. By 1735, Persia had defeated the Turkish-Tatar army, and the then leaders of Russian foreign policy, Levenvolde, Osterman and Biron, considered that the time had come to “repay Turkey for the Prut Peace, humiliating the honor of the Russian name.”

On July 23, 1735, the commander of the Russian troops, Field Marshal Munnich, received a letter from the Cabinet of Ministers with the order to open hostilities against the Ottoman Porte and the Crimean Khanate, for which the Russian troops should move from Poland, where they were then, to Ukraine and prepare for a campaign against the Crimean Tatars . The future Field Marshal Burdhard-Christoph Munnich was born on May 9, 1683 in the village of Neinguntorf, in the county of Oldenburg, which was then a Danish possession. The Minich family was a peasant, only his father Anton-Günther Minich received the noble dignity while serving in the Danish army. Burchard-Christoph Munnich entered the military service and rose to the rank of major general, while in the troops of Eugene of Savoy and the Duke of Marlborough. In February 1721, under Peter I, he entered the Russian service and arrived in St. Petersburg. Under Empress Anna Ioannovna, Minich became president of the military college.

Military operations against Turkey and the Crimean Khanate began in 1735 in the Crimea, and then moved to the borders of Bessarabia and Podolia. In August 1735, Minikh crossed the Don with his troops. Lieutenant General Leontiev with a corps of forty thousand, having dispersed small detachments of the Nogai Tatars, stopped ten days from Perekop and turned back. In March 1736, Russian troops began the siege of Azov.

On April 20, 1736, a fifty-thousand-strong Russian army, led by Minikh, set out from the town of Tsaritsynka, a former gathering place, and on May 20 entered the Crimea through Perekop, repelling the Crimean Khan with the army. The Perekop defensive line was an almost eight-kilometer ditch from the Azov to the Black Sea, about twelve meters wide and about ten meters deep, with a twenty-meter-high rampart, reinforced with six stone towers and the Perekop fortress with a Turkish Janissary garrison of two thousand people. Having stormed the Perekop fortifications, the Russian army went deep into the Crimea and ten days later entered Gezlev, capturing almost a month's supply of food for the entire army there. By the end of June, the troops approached Bakhchisaray, withstood two strong Tatar attacks in front of the Crimean capital, took the city, which had two thousand houses, and completely burned it along with the Khan's palace. After that, part of the Russian troops, passing to the Ak-Mechet, burned the empty capital of Kalga Sultan. At the same time, the ten thousandth Russian detachment of General Leontiev took Kinburn, which had a two thousandth Turkish garrison. The Russian troops of General Lassi also took Azov. After spending a month in the Crimea, the Russian troops withdrew to Perekop and returned to Ukraine at the end of autumn, having lost two thousand people directly from the fighting and half of the army from diseases and local conditions.

In retaliation for this, in February 1737, the Crimean Tatars raided the Ukraine across the Dnieper at Perevolochna, killing General Leslie and taking many prisoners.

In April 1737, the second campaign of Russian troops against the Turkish-Tatar possessions began. Having crossed the Dnieper and then the Bug, in mid-July, Minikh with seventy thousand Russian troops besieged and stormed Ochakov, in which they managed to blow up the powder magazines. Of the twenty thousand Turkish garrison, seventeen thousand people died, three thousand surrendered. Leaving a garrison in Ochakovo, the Russian troops returned to winter quarters in the Ukraine, as the Tatars burned the entire steppe, and, as always, the convoy with food appeared when the campaign was already over. The second twenty-five thousandth Russian detachment under the command of Field Marshal Lassi in early July 1737 crossed the Sivash ford, defeated and scattered the Crimean Tatar army led by the khan and took Karasubazar, a city of six thousand houses. Having devastated the city and about a thousand Tatar villages, the Russians returned through Milk Waters to Ukraine, deploying along the banks of the Northern Donets. During these campaigns of Russian troops in the Crimea, the Turkish sultan deposed the Crimean khans Kaplan Giray II and Fatih Giray. hiking Russian troops on the Crimean peninsula, large Tatar raids on Ukrainian and Russian lands were stopped. Large masses Tatars began to settle on the ground and engage in agriculture.

In October 1737, a united 40,000-strong Turkish-Tatar army under the command of the Bendery Pasha tried to recapture Ochakov, but after standing for two weeks in vain near the city, successfully defended by a 4,000-strong Russian garrison, went back.